For February 2018, Anne Bogel chose Maggie O’Farrell’s This Must Be The Place as the main book to read with Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies as the flight pick. I loved This Must Be The Place and now have a new author whose backlist I need to explore.

This Must Be The Place

What redemption there is in being loved: we are always our best selves when loved by another. Nothing can replace this.

Synopsis

In deciding how to describe this book, I pulled up Amazon to see how it was summarized. I don’t recommend you do this. This book gets billed as a love story—which I suppose it is, but if that’s your thing, This Must Be The Place will disappoint. At its heart, This Must Be The Place isn’t a love story so much as it’s a relationship story—a story of the relationship between two sets of children and their father, between a husband and wife, a son and his father, a man and the world around him that drives him to his knees.

Daniel, disappointed and alienated from his children, finds himself in Ireland retrieving his grandfather’s ashes when he stumbles upon Claudette Wells—THE Claudette Wells—famous actress/writer/producer turned recluse. As the two begin a relationship, the narrative travels back and forth in time, revealing what drove Claudette and Daniel to that back road in Ireland and what will ultimately drive them forward.

Structure & Writing

I adored This Must Be The Place. The chapters bounce around in time and viewpoint—most are straight narrative but some are correspondence, interview transcription, or auction lot descriptions. In many ways, the book reads as a series of interconnected short stories—this isn’t quite accurate since each of the chapters can’t stand entirely on their own, though many of them probably could. Because the story is being told in bits and afterthoughts from several characters introducing you to Claudette and Daniel from the side rather than head-on, the book is long. Many of the chapters had lengthy set up for what seemed perhaps like a minor payoff—some small part of Claudette revealed. And yet it was searching for these little payoffs—wondering how this chapter about adopting a child from China was going to introduce me to a piece of Claudette or Daniel’s life—that made the book so engaging for me. I searched for clues amidst the words. And yet, the writing was strong enough and the side-characters largely engaging enough that I didn’t mind the extra work. I enjoyed the ride. The comparison isn’t perfect since, as I noted, This Must Be The Place, isn’t truly a book of stories that can all stand on their own, but I found myself thinking of Olive Kitteridge. Some of the stories in Strout’s book feature Olive prominently and you learn quite a bit about her in one story. In others, she is the briefest of side characters and you read twenty pages to learn very little new about her. This is how some of the chapters were in The Must Be The Place.

This structure, however, is something that drove other readers in the MMD Book Club a little nuts. O’Farrell uses this technique well but it makes the book on long, non-standard-narrative and the payoff in some of the chapters is small. If this kind of device isn’t usually your thing, you may find This Must Be The Place to be meandering in a way that loses you. If this doesn’t usually bother you, then I highly recommend you give This Must Be The Place a try.

Characters

As I noted, the two main characters are Claudette—a famous actress who suddenly disappeared from public view one day—and Daniel, a somewhat ordinary man who stumbles upon her hiding place and becomes her husband. At first blush, it’s hard to feel sorry for Claudette—she’s a famous actress who could seemingly do no wrong in her writing and acting, beloved the world over. How hard could her life be? And yet, the farther you go, you see that the life Claudette fled was never the life she intended and it was far lonelier than it appeared on the outside. Her eccentricities are, in many ways, things she needed to do to feel a semblance of normalcy after her life grew out of her control.

Daniel seems to be the sympathetic character, the reasonable character, the character you want to cheer for. And yet, there comes a point towards the back third of the book when you realize that maybe you didn’t know him nearly as well as you thought you did. That there are things about his personality that call into question some of the earlier things he told the reader. It was a masterful change—one that was surprising and yet utterly not once the cards were on the table.

In Sum

I said it already—I adored this book. I’m glad I snapped up a copy when it was on sale on Kindle and I plan to go back into O’Farrell’s back list and read more of her work. Her writing was smart, at times funny and others pulling at my heartstrings, but never saccharine. If you know the narrative structure won’t be a distraction for you and you have time for a slightly longer (400 pages) book, give This Must Be The Place a read.

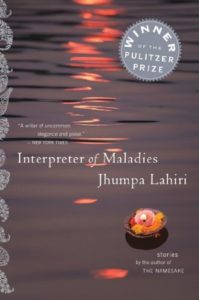

Interpreter of Maladies

…there are times I am bewildered by each mile I have traveled, each meal I have eaten, each person I have known, each room in which I have slept. As ordinary as it all appears, there are times when it is beyond my imagination.

Short Stories

When Anne Bogel chose Interpreter of Maladies as her flight pick for This Must Be The Place, I was pleased. I’ve owned this book and hadn’t had a chance to read it yet (#storyofmylife) and really enjoyed The Namesake when I read it several years ago. I’m glad I read Interpreter of Maladies, though I didn’t love it as much as I wanted to.

When Anne Bogel chose Interpreter of Maladies as her flight pick for This Must Be The Place, I was pleased. I’ve owned this book and hadn’t had a chance to read it yet (#storyofmylife) and really enjoyed The Namesake when I read it several years ago. I’m glad I read Interpreter of Maladies, though I didn’t love it as much as I wanted to.

While it’s billed as a series of loosely connected stories, Interpreter of Maladies is really a series of totally unconnected stories. The common thread—spider-silk thin—seems only to be that each character has been touched (some much more so than other) by the separation of Bengal (now Bangladesh) from India and Pakistan. Otherwise, there are no common characters and the stories are set in different times and places.

Short stories aren’t usually a genre I love—they’re usually too short to get me connected to a character and then just long enough for me to find them tedious since I don’t connect with anyone in what I’m reading. I would have told you I really disliked them before reading Strout’s Olive Kitteridge or Anything Is Possible last year. In some ways those stories are like reading This Must Be The Place—I’m getting glimpses here and there of the same character or characters and so the disconnect I usually feel with short stories is absent since I’m getting more common-character-payoff. The connection was ultimately too loose for me to feel about Interpreter the way I feel about Strout’s short stories.

I can recognize that Interpreter of Maladies is incredibly written—even though I don’t usually connect with short story characters, Interpreter had more pull than I usually find, such that I cared what happened to some of the characters more than I usually do in this form. The stories are descriptive without being gushy with compelling characters whose tragedies (because…it’s almost all little tragedies when the partition of India-Pakistan-Bangladesh is concerned) pull at your senses of what is right and fair. If short stories are your thing, this is a beautiful collection and I can see why it won the Pulitzer. I’d glad I read it and I may even read some of her other short stories to see if I like them as much or better, but this isn’t going on my top-ten list for 2018.

Featured image credit: Ferdinand Stöhr

Secret Daughter

Secret Daughter