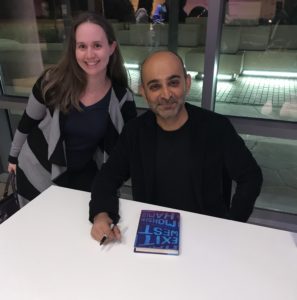

It has been a truly excellent fortnight of bookish events in Austin. The Mayor’s book club for the spring culminated in a reading and Q&A with Mohsin Hamid, author of Exit West—my absolute favorite book of 2017 and one of the my top-ten-of-all-time books (co-hosted by BookPeople, a fabulous indie bookstore in Austin). The Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas then hosted Colson Whitehead, author of The Underground Railroad, another phenomenal book and a top-ten read for 2017. My only regret is that I didn’t make it to Meg Wolitzer at BookPeople in between these two. I’m just finished The Female Persuasion—if I had been further into it and realized how much I liked it (but also how much I have questions about the whiteness), I probably would have made it happen.

Mohsin Hamid

Hamid began by reading a selection of his work—his speaking voice was measured and low and gave his words a haunting feel. The head of the Michener Center for Writers then began a dialogue during which I felt I couldn’t take notes fast enough.

Hamid talked about the idea of migrants—that “to be a migrant is to be a human being” and that we are all migrants through time. Everyone in  the modern world is, in many ways, in a state of transience—we experience life as a series of moments that are lost as the pass. As we pass through life we ultimately lose everything. And yet, while this is on the surface a depressing thought, when Hamid said it, it sounded mournful and yet beautiful. If everything is passing and we lose everything, why do we fight so hard to keep migrants out, to be the person who gets to define things like purity?

the modern world is, in many ways, in a state of transience—we experience life as a series of moments that are lost as the pass. As we pass through life we ultimately lose everything. And yet, while this is on the surface a depressing thought, when Hamid said it, it sounded mournful and yet beautiful. If everything is passing and we lose everything, why do we fight so hard to keep migrants out, to be the person who gets to define things like purity?

Exit West was, in part, a study on what it means for the dichotomy between migrant and native to evaporate. If the lines are fluid and all borders porous, these words lose their meaning. And if the dichotomy disappears, then so too must ideas like purity. Indeed, with the advances of technology—with cell phones as current, ubiquitous doors between worlds—ideas of religiosity vs. secularism and masculine vs. feminine are wearing thin. While some are reacting to this thinning by digging in and insisting on the divide, in Exit West Hamid explored what it means to have this dichotomy thin in a way that recognizes that you can move apart from ideas, from a place, from a person lovingly. That you can say goodbye without having to win.

With all of this loss, Exit West becomes a book about attrition (his words—of course. Because he is brilliant with words). His characters lose their country, their families, their homes, their technology, and ultimately even their identities as they once knew them. Here again Hamid returned to the idea that the basic predicament of human  life is that we lose everything—so what happens when he takes it all from his characters at an accelerated rate? And yet—as Exit West so lyrically and eloquently demonstrates, even amidst all of this loss, there is beauty and hope left. You can lose everything and still experience beauty, hope, and joy.

life is that we lose everything—so what happens when he takes it all from his characters at an accelerated rate? And yet—as Exit West so lyrically and eloquently demonstrates, even amidst all of this loss, there is beauty and hope left. You can lose everything and still experience beauty, hope, and joy.

Other driving forces for Hamid were the ideas of truth and decency. When we live in a world where everyone is trying to tell us there is no truth or decency, Hamid wrote a book where everything is exactly what it says it is (to us, the doors are metaphors but within the story the door is literally a door) and everyone is trying to be decent. In a world defined by loss but also truth and decency, these two are what enable that beauty and hope Hamid wants us to see is still in the world.

The final theme that came up repeatedly was the idea of purity. In concept, it seems like such a good thing—purity, cleanness, inviolate. And yet, in real life, purity is very rarely a good thing. Rather it is a weapon that inspires shame at best and violence at worst. Hamid noted that “if we are to live in a world where purity is valued and migrants are bad, then there is no place for me.” We have to recognize purity for the dangerous construct that it is.

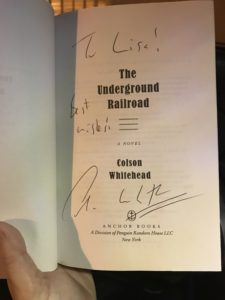

Colson Whitehead

Like Hamid, Whitehead began by reading a selection from his work –in this case, The Underground Railroad—but this is where their talks diverged. In contrast to Hamid, Whitehead was remarkably funny and self-deprecating—not what I  expected. (Though, to be fair, I hadn’t read up on Whitehead besides reading his work—no interviews, no videos, no visit to his website. I supposed I expected the writer of a Pulitzer and National Book Award winning book to be serious and speak with furrowed brows—like a serious person with a serious forehead.)

expected. (Though, to be fair, I hadn’t read up on Whitehead besides reading his work—no interviews, no videos, no visit to his website. I supposed I expected the writer of a Pulitzer and National Book Award winning book to be serious and speak with furrowed brows—like a serious person with a serious forehead.)

Instead, Whitehead talked about becoming a writer because it meant he could never leave the house, stay in his pajamas, and not talk to people. (These are also the top three reasons I too would become a writer if I could.) His brow furrowed only when interrupting people in the audience who, in the midst of their questions, prepared to spoil some twist or turn in the book.

I enjoyed his backstory in that I didn’t get any of this sense of personality or humor from The Underground Railroad (for rather obvious reasons). When discussing why he writes about the characters he does he noted, that he “could have written a book about an upper middle class white person who feels sad sometimes but there’s a lot of competition” for that book. When he talked about being a writer, he said that you should just accept that “no matter what you are working on—a book about slavery, etc.—someone smarter and better than you has already written it.” Just accept that. And then “don’t focus on them. Focus on you.” If you know someone has already done it better, there’s no pressure to be the best. There’s just the pressure to write as you on this topic.

He then turned t o discussing The Underground Railroad more directly. While writing a book about the Railroad occurred to him early, he waited—he talked about not being a good enough writer yet and saving this idea until he could do it justice. He talked about the States being states of American possibility and drawing broader connections to other historical events. In North Carolina when Cora hides in the attic from the people who would kill her, this felt reminiscent of Anne Frank—this was, in fact deliberate. Having North Carolina presented the way it did was a deliberate effort to make a connection to Nazi Germany where the Nazis apparently studied American slavery and racism, using some of our language as their model.

o discussing The Underground Railroad more directly. While writing a book about the Railroad occurred to him early, he waited—he talked about not being a good enough writer yet and saving this idea until he could do it justice. He talked about the States being states of American possibility and drawing broader connections to other historical events. In North Carolina when Cora hides in the attic from the people who would kill her, this felt reminiscent of Anne Frank—this was, in fact deliberate. Having North Carolina presented the way it did was a deliberate effort to make a connection to Nazi Germany where the Nazis apparently studied American slavery and racism, using some of our language as their model.

Whitehead also discussed Cora, the main character and her being the most different from him than any of his other protagonists. He noted that if you are writing and your protagonist is coming too easy, then you are probably not putting in the work you need to in developing his or her character. In other places, his characters served as plot devices—he needed Ridgeway to be a slave catcher and to drive certain plot events forward. So he included him to move the plot and then figured out who he was as a character and came back and filled him out later—indeed, the vignette of Ridgeway was apparently one of the last-written sections for this reason. It is important to note, however, that you do actually have to come back. You can’t just put in a character to move the plot forward and never come back to them to see how they walk and talk.

The other quote Whitehead left me with is that he “owes no responsibility to the reader.” He mentioned this within the context of questions he often receives. Apparently he is frequently asked about whether he feels responsible for what people know or how their sense of history is altered (possibly incorrectly if they read The Underground Railroad too literally) and he vehemently noted that he doesn’t owe anything to his readers in this sense. I appreciated this stance. While I don’t think it applies to everyone—there are people writing morally reprehensible things, words that are then put to ill use in violent ideologies and those people are responsible (see previous note re: slavery and Nazis); however, for someone writing fiction like Whitehead this is true. His work is not inciting violence or hatred—he therefore doesn’t owe the reader any obligation to stick solely to the truth in presenting his world and his characters. There is a difference between being true to the time period in which one writes the book and being so slavish that one cannot include magical realist elements like an actual underground railroad.

The other quote Whitehead left me with is that he “owes no responsibility to the reader.” He mentioned this within the context of questions he often receives. Apparently he is frequently asked about whether he feels responsible for what people know or how their sense of history is altered (possibly incorrectly if they read The Underground Railroad too literally) and he vehemently noted that he doesn’t owe anything to his readers in this sense. I appreciated this stance. While I don’t think it applies to everyone—there are people writing morally reprehensible things, words that are then put to ill use in violent ideologies and those people are responsible (see previous note re: slavery and Nazis); however, for someone writing fiction like Whitehead this is true. His work is not inciting violence or hatred—he therefore doesn’t owe the reader any obligation to stick solely to the truth in presenting his world and his characters. There is a difference between being true to the time period in which one writes the book and being so slavish that one cannot include magical realist elements like an actual underground railroad.

Conclusion

I’m not one of those “leave the house” kind of people. A good night for me is the Thai takeout from just up the street, a Red Sox game on mute on the television, book in hand, puppy on lap (or more likely puppy on feet, puppy on lap, and third puppy begging to be petted at my side because while I’ll never be a cat lady, my descent into puppy-lady has begun). While I wound up meeting some other Modern Mrs. Darcy book clubbers at Mohsin Hamid, my plan for that one was actually to go by myself before I realized others were going. And I went to Colson Whitehead by myself. Normally, I’d look at an event like this and plan to go but then the night of, already be in pajama pants and decide re-dressing and leaving my house wasn’t worth it.

And yet, I would miss out on experiences like hearing both of these men. Both of these talks wound up being the highlight of my week. I’ll probably still never be a movie by myself kind of person (I’ve done it once), I need to remember how lovely these two experiences were. If you have a chance to see an author you love, I encourage you to go—to put real pants back on, pay that $6 to park downtown, and go hear the words of the person who wrote this book you love. I’m certainly glad I did.

Header/Featured Photo Credit: Marcos Luiz Photograph