August was a fair amount of reading but not so much with the writing of blog posts. I had good intentions. They were not realized. Birthday pass?

I finished ten books this month–There There, Drums of Autumn, Fruit of the Drunken Tree, Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions, Instructions for a Heat Wave, The Round House, Heads of the Colored People, The Dinner List, I am I am I am, and My Real Name is Hanna. Thanks to that Gabaldon tome, my monthly total was 2,597 pages for a year total of 20,678 pages. The three audio books–There There, Instructions for a Heatwave, and I am I am I am–clocked in at 23 hours and 2 minutes for a year total of 208 hours and 29 minutes. Not too shabby for the old birth month.

I also acquired more books than I want to think about because it’s my party and I’ll buy books if I want to. I’ll spare you the list but you should be impressed that I still have Amazon credit left.

The Dinner List

The Dinner List was a Book of the Month* pick for August and comes out on September 11th. I hemmed and hawed over my box last month, trying to decide which books I wanted to get. I actually hemmed and hawed so much that other people in a BOTM Facebook group I’m in received their books and started talking about them. I try to make my BOTM picks books I think I will want to re-read since I’m making the splurge and getting them in a physical copy. The Dinner List is lighter than my usual BOTM fare and yet I’m glad I took a chance and picked it as an extra. I picked it up last weekend in the middle of two crazy weeks at work and it was exactly the distraction I needed.

The Dinner List was a Book of the Month* pick for August and comes out on September 11th. I hemmed and hawed over my box last month, trying to decide which books I wanted to get. I actually hemmed and hawed so much that other people in a BOTM Facebook group I’m in received their books and started talking about them. I try to make my BOTM picks books I think I will want to re-read since I’m making the splurge and getting them in a physical copy. The Dinner List is lighter than my usual BOTM fare and yet I’m glad I took a chance and picked it as an extra. I picked it up last weekend in the middle of two crazy weeks at work and it was exactly the distraction I needed.

The premise is fairly simple and reminiscent of an icebreaker game you were probably forced to play at summer camp–name any five people, living or dead, you’d like to have dinner with. Thus begins Sabrina’s thirtieth birthday with her best friend, Audrey Hepburn, her ex-boyfriend Tobias, and a few others. Serle does an excellent job weaving the connections to Audrey Hepburn into the book so that the choice of Ms. Hepburn at the table feels less random than it could, or the throwaway choice every girl who had A Breakfast at Tiffany’s poster on her dorm room wall would make (guilty as charged). And, as Anne Bogel noted, Audrey makes it work–she brings levity and a bit of magical whimsy to otherwise heavy moments, yet her own actual tragic history brings perspective to others.

I went into The Dinner List wanted an easy escape read and discovered a surprisingly poignant gem. The writing gave me the easy escape I wanted, the premise made the plot move fast enough to stay compelling, and the characters made me care deeply for each of them. The Dinner List probes the reasons people leave, why certain people seem drawn to our lives, and what it means to let go.

Notes

Published: September 11, 2018 by Flatiron Books (@flatiron_books)

Author: Rebecca Serle

Date read: August 25, 2018

Rating: 4 stars

Cupcake header photo credit: Audrey Fretz

*This is a referral link. I’ll get a free book if you decide to try it out. There are always deals going on for a free tote and/or free book. I’d love to chat if you want to know more, but no pressure. <3

Census was one of the Modern Mrs. Darcy Summer Reading Guide Picks. While Anne frequently picks books that are literary (as opposed to just pop-fiction) and full of discussion-fodder, this one is the first one that I can remember thinking might have just been entirely over my head. On its face, Census was the story of a dying widower who takes his son with down syndrome on one last trip through the country. They travel from town to town–in order named A through Z–taking the “census” which involves asking a series of never-revealed questions and then leaving a tattoo on the ribs of the person from whom the census was taken. There’s a vaguely sinister feel to the census-taking and I was left with the sense that it stood for something larger….though I’m not sure for the life of me what it was. The book raises questions around the themes of kindness and how we treat people with disabilities, though Ball never provides the answers as to how we should treat people. He simply shows how we do. I was left with the impression that Census was beautiful and haunting but that there had to be something more to it that I was missing. I still don’t know what it was.

Census was one of the Modern Mrs. Darcy Summer Reading Guide Picks. While Anne frequently picks books that are literary (as opposed to just pop-fiction) and full of discussion-fodder, this one is the first one that I can remember thinking might have just been entirely over my head. On its face, Census was the story of a dying widower who takes his son with down syndrome on one last trip through the country. They travel from town to town–in order named A through Z–taking the “census” which involves asking a series of never-revealed questions and then leaving a tattoo on the ribs of the person from whom the census was taken. There’s a vaguely sinister feel to the census-taking and I was left with the sense that it stood for something larger….though I’m not sure for the life of me what it was. The book raises questions around the themes of kindness and how we treat people with disabilities, though Ball never provides the answers as to how we should treat people. He simply shows how we do. I was left with the impression that Census was beautiful and haunting but that there had to be something more to it that I was missing. I still don’t know what it was. Barracoon, originally written by Zora Neale Hurston but with added introductory information, is one of those books that I think is a must-read (or listen). While still a fairly young writer, Hurston met Cudjo Lewis, the last living slave brought from Africa and transcribed his recollections of life in what is now Benin, the Middle Passage, and slavery in America before the outbreak of war. As I noted above, this is short–it’s under four hours when performed, including all of the introductory material. It was a tad hard to follow simply because this is the kind of book that has words that aren’t common to English and because Hurston transcribed Mr. Lewis’s accent and vernacular phonetically, though it didn’t take long for me to settle in to the language, so don’t let that turn you off. Given the dearth of available primary sources from Africans and African Americans during this time period (relative to the histories written by white men), this is a book that should be on every reading list and in everyone’s hands.

Barracoon, originally written by Zora Neale Hurston but with added introductory information, is one of those books that I think is a must-read (or listen). While still a fairly young writer, Hurston met Cudjo Lewis, the last living slave brought from Africa and transcribed his recollections of life in what is now Benin, the Middle Passage, and slavery in America before the outbreak of war. As I noted above, this is short–it’s under four hours when performed, including all of the introductory material. It was a tad hard to follow simply because this is the kind of book that has words that aren’t common to English and because Hurston transcribed Mr. Lewis’s accent and vernacular phonetically, though it didn’t take long for me to settle in to the language, so don’t let that turn you off. Given the dearth of available primary sources from Africans and African Americans during this time period (relative to the histories written by white men), this is a book that should be on every reading list and in everyone’s hands. Quite literally the day after I posted a mini-review of Still Lives on Instagram, Reese Witherspoon picked it for her August book club pick. I guess Reese and I have slightly different taste. I’ve said it before but thrillers, unless they raise questions like those in

Quite literally the day after I posted a mini-review of Still Lives on Instagram, Reese Witherspoon picked it for her August book club pick. I guess Reese and I have slightly different taste. I’ve said it before but thrillers, unless they raise questions like those in

The Ensemble is one of those books that getting a lot of hype—more than one book subscription chose it this summer, Girls Night In chose it for their July read, and Modern Mrs. Darcy chose it as one of her Summer Reading Guide books. This is a book that, for once, mostly holds up to that hype. The Ensemble follows leader Jana, prodigy Henry, scrappy Daniel, and quiet Brit—the Van Ness Quartet—over the span of almost twenty years making music together.

The Ensemble is one of those books that getting a lot of hype—more than one book subscription chose it this summer, Girls Night In chose it for their July read, and Modern Mrs. Darcy chose it as one of her Summer Reading Guide books. This is a book that, for once, mostly holds up to that hype. The Ensemble follows leader Jana, prodigy Henry, scrappy Daniel, and quiet Brit—the Van Ness Quartet—over the span of almost twenty years making music together. Far From The Tree is the story of three siblings, separated at birth—Grace and Maya were both relinquished at their births while Joaquin was removed from their mother’s care around age 1. None of them knew about each other before now. While Grace and Maya seem to have had it “easy” by being adopted, you quickly realize that families are complicated, whether formed by choice or blood. Joaquin, having been in foster care for almost seventeen years, seems to finally have it good and yet, people can always disappoint you. As the three come together and begin to search for their birth mom, the search will turn up more than any of them ever expected.

Far From The Tree is the story of three siblings, separated at birth—Grace and Maya were both relinquished at their births while Joaquin was removed from their mother’s care around age 1. None of them knew about each other before now. While Grace and Maya seem to have had it “easy” by being adopted, you quickly realize that families are complicated, whether formed by choice or blood. Joaquin, having been in foster care for almost seventeen years, seems to finally have it good and yet, people can always disappoint you. As the three come together and begin to search for their birth mom, the search will turn up more than any of them ever expected. Goodbye, Vitamin is thirty-year old Ruth’s chronicle of an unexpected year at home following the end of her engagement and her father’s diagnosis with early-onset Alzheimer’s. As a child, Ruth’s father kept a small diary of funny things she said and did, little milestones. Ruth’s documenting of this year at home is the reverse—while she does write much about her own life (particularly at the beginning during the set up), as she settles into life in her parents’ house again, she chronicles her father’s life. His moments of brilliance even as the disease progresses. As the year goes by and Ruth finds her place again with a family she had lost connection to, Ruth writes less until the last chapters have only a few entries per month. Goodbye, Vitamin is poignant and short—I actually felt it was a little too short. I think Khong’s point was that Ruth was reforming her connections to her family and to what life could be as she wrote—as Ruth actually engaged with them, she spent less time writing. What it felt like was that Khong ran out of steam and the book petered out. This really was my only criticism. Ruth won’t be everyone’s favorite protagonist—in many ways she has the sense of life happening to her rather than having agency in her choices as the book opens (I mean this more about her job and place in life, and not in her fiancé’s being a total ass). I wasn’t wild about her as the book began, but I stuck with it and she leveled out for me and I grew to care about her a few “months” (chapters) into the book and, by the end, wanted more of her.

Goodbye, Vitamin is thirty-year old Ruth’s chronicle of an unexpected year at home following the end of her engagement and her father’s diagnosis with early-onset Alzheimer’s. As a child, Ruth’s father kept a small diary of funny things she said and did, little milestones. Ruth’s documenting of this year at home is the reverse—while she does write much about her own life (particularly at the beginning during the set up), as she settles into life in her parents’ house again, she chronicles her father’s life. His moments of brilliance even as the disease progresses. As the year goes by and Ruth finds her place again with a family she had lost connection to, Ruth writes less until the last chapters have only a few entries per month. Goodbye, Vitamin is poignant and short—I actually felt it was a little too short. I think Khong’s point was that Ruth was reforming her connections to her family and to what life could be as she wrote—as Ruth actually engaged with them, she spent less time writing. What it felt like was that Khong ran out of steam and the book petered out. This really was my only criticism. Ruth won’t be everyone’s favorite protagonist—in many ways she has the sense of life happening to her rather than having agency in her choices as the book opens (I mean this more about her job and place in life, and not in her fiancé’s being a total ass). I wasn’t wild about her as the book began, but I stuck with it and she leveled out for me and I grew to care about her a few “months” (chapters) into the book and, by the end, wanted more of her.

I came across Monster in a list at the library about books for Black History month, in a If-You-Liked-The-Hate-U-Give-You’ll-Like-This list. I would agree that it makes a good flight pick along with Dear Martin and The Hate U Give. The three books consider similar themes and provide alternative sides to a similar experience. Unlike the other two, however, Monster is the story of a teenager who wasn’t killed by police, but rather has been accused of felony murder for allegedly participating in a robbery gone wrong that left a man dead. The book is written in first person narrated by Steve Harmon, the child accused of the crime–however, in order to cope with what is happening, Steve presents it as if he is writing a film for one of his classes. The entire book reads like a screenplay. This unusual device works, providing the remove Steve need to tell his story while still giving the reader a sense of what is happening around him. Frankly, it also makes the book incredibly quick to read relative to the page length–I think I finished it in under two hours. The book won the first Michael L. Printz Award (best book in teen literature), ALA Best Book honors, Coretta Scott King honors, and was a finalist for the National Book Award when it was published. It was a powerful book, even more so for the unexpected gut-punch in the last few pages. Just when I thought I could breathe, Walter Dean Myers delivered one last visceral blow that was true to the book and true to how black boys are treated in this country. It’s not an easy read but one I recommend.

I came across Monster in a list at the library about books for Black History month, in a If-You-Liked-The-Hate-U-Give-You’ll-Like-This list. I would agree that it makes a good flight pick along with Dear Martin and The Hate U Give. The three books consider similar themes and provide alternative sides to a similar experience. Unlike the other two, however, Monster is the story of a teenager who wasn’t killed by police, but rather has been accused of felony murder for allegedly participating in a robbery gone wrong that left a man dead. The book is written in first person narrated by Steve Harmon, the child accused of the crime–however, in order to cope with what is happening, Steve presents it as if he is writing a film for one of his classes. The entire book reads like a screenplay. This unusual device works, providing the remove Steve need to tell his story while still giving the reader a sense of what is happening around him. Frankly, it also makes the book incredibly quick to read relative to the page length–I think I finished it in under two hours. The book won the first Michael L. Printz Award (best book in teen literature), ALA Best Book honors, Coretta Scott King honors, and was a finalist for the National Book Award when it was published. It was a powerful book, even more so for the unexpected gut-punch in the last few pages. Just when I thought I could breathe, Walter Dean Myers delivered one last visceral blow that was true to the book and true to how black boys are treated in this country. It’s not an easy read but one I recommend. I’ll admit that I was hoping for an adult Westing Game –this wasn’t that. (Though it’s probably being unfair to hope for another Westing Game.) This was a fun little diversion–a thriller set in the midst of a highly dysfunctional family after the patriarch dies. (I guess novels set in well-functioning families don’t typically produce enough plot to merit books?). Jacobs had a knack for presenting most of the characters in fairly well-rounded ways–even the minor characters weren’t flat or simply plot devices. As a result I managed to sympathize with almost all of the characters–even the bad actors and hate everyone at some point–kind of how I feel about real people. No one is perfect, everyone has their own internal motivations, and someone is always going to make a choice that I disagree with. Though the sub-title of the book is “A Novel In Clues” and the book is about a mathematician, absolutely no math background is necessary to enjoy this book. It wasn’t the best thriller but it was a diversion when I needed one and may be worth checking out if mysteries are your wheelhouse. Though there’s a fair amount of death, there’s no gore.

I’ll admit that I was hoping for an adult Westing Game –this wasn’t that. (Though it’s probably being unfair to hope for another Westing Game.) This was a fun little diversion–a thriller set in the midst of a highly dysfunctional family after the patriarch dies. (I guess novels set in well-functioning families don’t typically produce enough plot to merit books?). Jacobs had a knack for presenting most of the characters in fairly well-rounded ways–even the minor characters weren’t flat or simply plot devices. As a result I managed to sympathize with almost all of the characters–even the bad actors and hate everyone at some point–kind of how I feel about real people. No one is perfect, everyone has their own internal motivations, and someone is always going to make a choice that I disagree with. Though the sub-title of the book is “A Novel In Clues” and the book is about a mathematician, absolutely no math background is necessary to enjoy this book. It wasn’t the best thriller but it was a diversion when I needed one and may be worth checking out if mysteries are your wheelhouse. Though there’s a fair amount of death, there’s no gore. Queen of Hearts is being billed as Grey’s Anatomy in book form. This is….accurate-ish. There’s less going on in Queen of Hearts since Martin is working with less space than a Grey’s Anatomy season and the drama is (mostly) in the past, just come to revisit Zadie and Emma. They’ve had a good run with relatively little drama since their intern years in medical school a decade ago, but that doesn’t make a good book. Enter stage left, Zadie’s McDreamy from her first intern year, bearing secrets for what really happened ten years ago. The book was deliciously fluffy and dramatic, had some mystery elements (what really happened that year?), but stayed pretty well in the popular fiction lane. I was bothered twice by body-shaming comments made about people who were overweight. This wasn’t surprising giving that Martin is herself a doctor and health professionals often seem particularly prone to assuming size is indicative of health, but was disappointing and distracting. It also ended a bit too neatly (which is not the same as happily) for me–I think Martin could have left a few loose ends hanging and it would have felt more true to life. Ultimately, if you’re looking for a fluffy, plot-driven beach read, Queen of Hearts is a good one.

Queen of Hearts is being billed as Grey’s Anatomy in book form. This is….accurate-ish. There’s less going on in Queen of Hearts since Martin is working with less space than a Grey’s Anatomy season and the drama is (mostly) in the past, just come to revisit Zadie and Emma. They’ve had a good run with relatively little drama since their intern years in medical school a decade ago, but that doesn’t make a good book. Enter stage left, Zadie’s McDreamy from her first intern year, bearing secrets for what really happened ten years ago. The book was deliciously fluffy and dramatic, had some mystery elements (what really happened that year?), but stayed pretty well in the popular fiction lane. I was bothered twice by body-shaming comments made about people who were overweight. This wasn’t surprising giving that Martin is herself a doctor and health professionals often seem particularly prone to assuming size is indicative of health, but was disappointing and distracting. It also ended a bit too neatly (which is not the same as happily) for me–I think Martin could have left a few loose ends hanging and it would have felt more true to life. Ultimately, if you’re looking for a fluffy, plot-driven beach read, Queen of Hearts is a good one.

Force of Nature is the second offering from Australian Jane Harper and continues to follow Detective Aaron Falk (or whatever Australians call detectives—I don’t have the book anymore as I had to return it to the library.) This one seemed to follow Aaron less (a little less need to introduce him to the reader in the second book) and stuck fairly close to the story of a team-building camping trip gone very, very wrong. I use mystery/thrillers like palate cleansers—when I’ve read a lot of heavy books and don’t want to think too hard and just want entertainment, they’re perfect. With this in mind, Force of Nature was a fun diversion with a few twists that kept it from being predictable. The Australian setting, particularly this time, felt like an exotic adventure from my couch. I think each of Harper’s books stands alone and don’t necessarily need to be read in order, though knowing who Falk is from the first book made the second easier to read—without it, I’m not sure you’d care as much about him.

Force of Nature is the second offering from Australian Jane Harper and continues to follow Detective Aaron Falk (or whatever Australians call detectives—I don’t have the book anymore as I had to return it to the library.) This one seemed to follow Aaron less (a little less need to introduce him to the reader in the second book) and stuck fairly close to the story of a team-building camping trip gone very, very wrong. I use mystery/thrillers like palate cleansers—when I’ve read a lot of heavy books and don’t want to think too hard and just want entertainment, they’re perfect. With this in mind, Force of Nature was a fun diversion with a few twists that kept it from being predictable. The Australian setting, particularly this time, felt like an exotic adventure from my couch. I think each of Harper’s books stands alone and don’t necessarily need to be read in order, though knowing who Falk is from the first book made the second easier to read—without it, I’m not sure you’d care as much about him. I Was Anastasia left me wanting to know more about the Romanovs so I wound up picking up The Romanov Sisters from the library after I finished that one. I think almost to the day that I finished reading Lawhon’s book, Anne Bogel posted a match up recommending it as a companion read. I took it as fate and picked it up. It was a bit dense for a pleasure read—Rappaport heavily footnotes her sources (as she should!) and uses extensive quotes. It was surprisingly readable for what it was, which felt much more like an academic text than a narrative nonfiction meant for a mass audience. I’m not sorry I read it since this is a gaping hole in my historical knowledge, but it was kind of niche—I’m not sure how knowing about three year old Alexey Romanov is going to help me in the future.

I Was Anastasia left me wanting to know more about the Romanovs so I wound up picking up The Romanov Sisters from the library after I finished that one. I think almost to the day that I finished reading Lawhon’s book, Anne Bogel posted a match up recommending it as a companion read. I took it as fate and picked it up. It was a bit dense for a pleasure read—Rappaport heavily footnotes her sources (as she should!) and uses extensive quotes. It was surprisingly readable for what it was, which felt much more like an academic text than a narrative nonfiction meant for a mass audience. I’m not sorry I read it since this is a gaping hole in my historical knowledge, but it was kind of niche—I’m not sure how knowing about three year old Alexey Romanov is going to help me in the future. ood House

ood House

Hunger is Roxane Gay’s most recent work—a series of essays of varying lengths about food, her body, and hunger—for what she can and can’t have. Unlike Bad Feminist, Gay reads Hunger herself—an addition that made the audiobook more powerful than the text alone and why I went ahead and used the Audible credit. This is a book I think I will need to revisit a few times to really experience Gay’s writing and argument, largely because of the power and nuance here. I don’t want to assume I got everything out of this book the first time.

Hunger is Roxane Gay’s most recent work—a series of essays of varying lengths about food, her body, and hunger—for what she can and can’t have. Unlike Bad Feminist, Gay reads Hunger herself—an addition that made the audiobook more powerful than the text alone and why I went ahead and used the Audible credit. This is a book I think I will need to revisit a few times to really experience Gay’s writing and argument, largely because of the power and nuance here. I don’t want to assume I got everything out of this book the first time. The other book I read but didn’t plan to fully review this month was Claire Messud’s The Burning Girl. The Burning Girl is the story of childhood best-friends Julia and Cassie in the years between late middle school and early high school or, rather, it’s the story of how Julia and Cassie fall apart. Of how growing up can often be the fracturing of the “forever” you thought as an essential and automatic part of the BFF moniker.

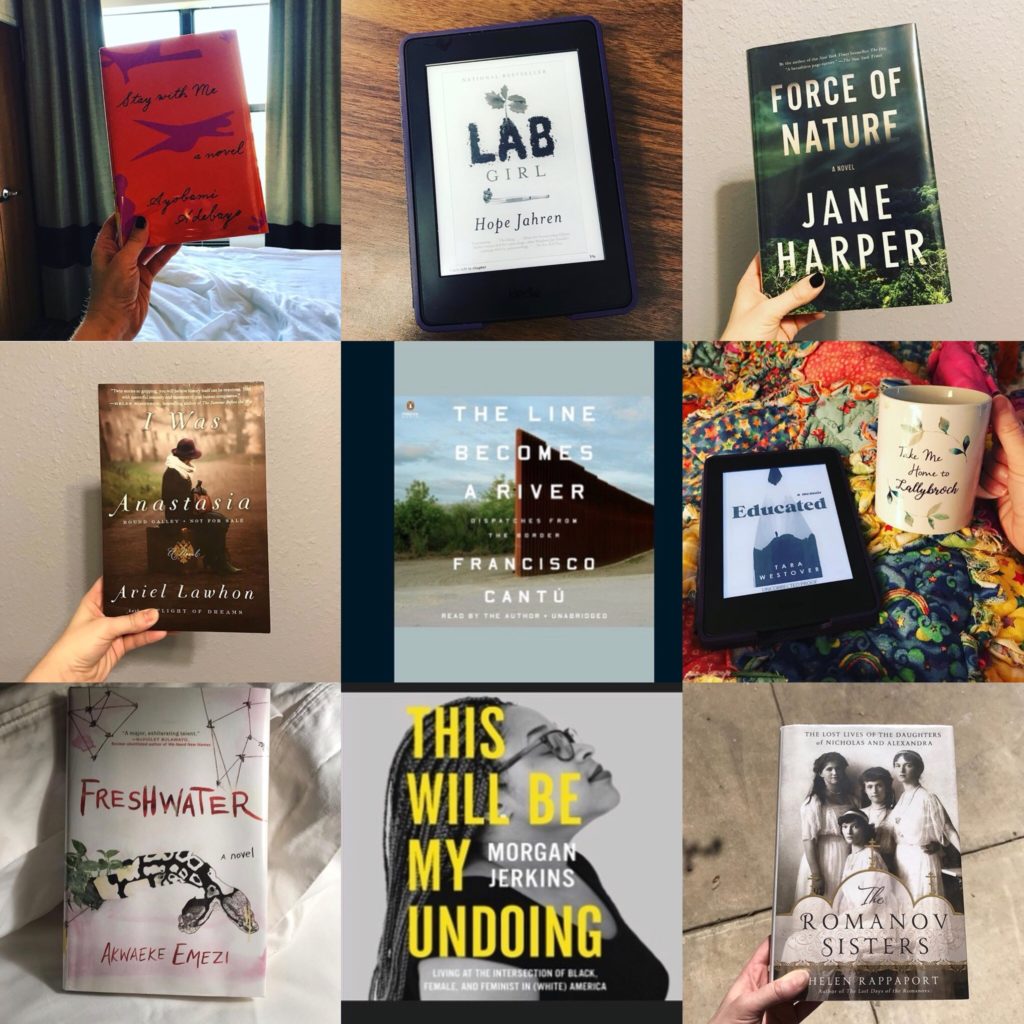

The other book I read but didn’t plan to fully review this month was Claire Messud’s The Burning Girl. The Burning Girl is the story of childhood best-friends Julia and Cassie in the years between late middle school and early high school or, rather, it’s the story of how Julia and Cassie fall apart. Of how growing up can often be the fracturing of the “forever” you thought as an essential and automatic part of the BFF moniker. ’ve picked another ten books for March, though a bunch of books I was excited about came in at the library so I’m just barely paying lip service to #theunreadshelfproject this month. I have already finished Stay With Me (MMD March pick) and Force of Nature, the second Aaron Falk mystery from Jane Harper and its only the fifth, so the month is starting off strong. I also hope to finish Freshwater, Lab Girl (DBC), My Life On the Road (audio), I Was Anastasia, Priestdaddy, Oliver Loving, and The Hazel Wood. Of those, I own only My Life On the Road, I Was Anastasia, and Priestdaddy. I’ve also got Finding Wonders as the Middle Grade pick for DBC, though with Middle Grade being hit-or-miss for me, I’ve picked up Home Fire, the April MMD book, to start early if I finish all those or wind up DNF-ing Finding Wonders. The other MMD pick this month is Americanah which I listened to last year on audio and thought was lovely, but wasn’t going to re-read so soon.

’ve picked another ten books for March, though a bunch of books I was excited about came in at the library so I’m just barely paying lip service to #theunreadshelfproject this month. I have already finished Stay With Me (MMD March pick) and Force of Nature, the second Aaron Falk mystery from Jane Harper and its only the fifth, so the month is starting off strong. I also hope to finish Freshwater, Lab Girl (DBC), My Life On the Road (audio), I Was Anastasia, Priestdaddy, Oliver Loving, and The Hazel Wood. Of those, I own only My Life On the Road, I Was Anastasia, and Priestdaddy. I’ve also got Finding Wonders as the Middle Grade pick for DBC, though with Middle Grade being hit-or-miss for me, I’ve picked up Home Fire, the April MMD book, to start early if I finish all those or wind up DNF-ing Finding Wonders. The other MMD pick this month is Americanah which I listened to last year on audio and thought was lovely, but wasn’t going to re-read so soon.

definitely keeping. Set in the near future after a killer flu wipes out 99% of the world’s population (taking down with it all manufacturing, electricity, etc.), Station Eleven follows a traveling Shakespearean theater company and orchestra as they travel the shores of Lake Michigan going from town to town performing. Their travels are going as planned, until the arrival of a violent prophet threatens their safety and way of life. Station Eleven is beautifully written with just the right amount of creepy detail–like the plane that was prohibited from disembarking in the airport so that twenty years later, it still stands sealed full of flu victims on the far edge of the airport tarmac. Overall, the book has some dark details but is not depressing, a feat for Mandel since Station Eleven could easily have gone off the deep end of dark. Her characters are flawed people but resilient–if we’re being cliche, Station Eleven is, at its heart, not only a story of the collapse of civilization and the dangerous directions that can take, but also of the indomitable nature of the human spirit. Mandel seemed to have thought of everything that life after the collapse of technology would mean but doesn’t lecture. She’s a master of showing rather than telling. The book is relatively short–just over 300 pages–and yet the amount of story and character development she manages to fit into those pages is impressive. If you missed this one a few years ago like I did, I highly recommend you remedy your oversight and pick this one up.

definitely keeping. Set in the near future after a killer flu wipes out 99% of the world’s population (taking down with it all manufacturing, electricity, etc.), Station Eleven follows a traveling Shakespearean theater company and orchestra as they travel the shores of Lake Michigan going from town to town performing. Their travels are going as planned, until the arrival of a violent prophet threatens their safety and way of life. Station Eleven is beautifully written with just the right amount of creepy detail–like the plane that was prohibited from disembarking in the airport so that twenty years later, it still stands sealed full of flu victims on the far edge of the airport tarmac. Overall, the book has some dark details but is not depressing, a feat for Mandel since Station Eleven could easily have gone off the deep end of dark. Her characters are flawed people but resilient–if we’re being cliche, Station Eleven is, at its heart, not only a story of the collapse of civilization and the dangerous directions that can take, but also of the indomitable nature of the human spirit. Mandel seemed to have thought of everything that life after the collapse of technology would mean but doesn’t lecture. She’s a master of showing rather than telling. The book is relatively short–just over 300 pages–and yet the amount of story and character development she manages to fit into those pages is impressive. If you missed this one a few years ago like I did, I highly recommend you remedy your oversight and pick this one up. t only how he came to grips with his brother’s death but also how schizophrenia slowly started to take hold of his life. This book could easily have gone off the rails, but the tone was overall respectful. I cared deeply for Matthew and Filer handled Matthew’s refusal of his medication in a way that the reader could understand why he was making this choice that is usually portrayed as incomprehensible. ::sidebar:: There are many and valid reasons people with mental illness don’t want to take their medications, just like there are many reasons people with health conditions don’t take their doctors’ advice or take medications as prescribed. ::end sidebar:: If nothing else, The Shock of the Fall shows how grief is a universal emotion, though the experience and the struggle of it is not universally the same.

t only how he came to grips with his brother’s death but also how schizophrenia slowly started to take hold of his life. This book could easily have gone off the rails, but the tone was overall respectful. I cared deeply for Matthew and Filer handled Matthew’s refusal of his medication in a way that the reader could understand why he was making this choice that is usually portrayed as incomprehensible. ::sidebar:: There are many and valid reasons people with mental illness don’t want to take their medications, just like there are many reasons people with health conditions don’t take their doctors’ advice or take medications as prescribed. ::end sidebar:: If nothing else, The Shock of the Fall shows how grief is a universal emotion, though the experience and the struggle of it is not universally the same. north). Several of them read and mentioned this book one-after-another so I picked it up this month. It’s a narrative nonfiction story about the essentially uninvestigated, suspicious deaths of First Nation children who were sent away for school in Canada. As part of the narrative, Talaga provides background on the racist residential school system designed to destroy indigenous families and cultures (it was literally a model for apartheid South Africa) as well as revealing the rampant racism still prevalent against indigenous peoples in Canada today (Et tu, Canada?).

north). Several of them read and mentioned this book one-after-another so I picked it up this month. It’s a narrative nonfiction story about the essentially uninvestigated, suspicious deaths of First Nation children who were sent away for school in Canada. As part of the narrative, Talaga provides background on the racist residential school system designed to destroy indigenous families and cultures (it was literally a model for apartheid South Africa) as well as revealing the rampant racism still prevalent against indigenous peoples in Canada today (Et tu, Canada?).