August was a fair amount of reading but not so much with the writing of blog posts. I had good intentions. They were not realized. Birthday pass?

I finished ten books this month–There There, Drums of Autumn, Fruit of the Drunken Tree, Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions, Instructions for a Heat Wave, The Round House, Heads of the Colored People, The Dinner List, I am I am I am, and My Real Name is Hanna. Thanks to that Gabaldon tome, my monthly total was 2,597 pages for a year total of 20,678 pages. The three audio books–There There, Instructions for a Heatwave, and I am I am I am–clocked in at 23 hours and 2 minutes for a year total of 208 hours and 29 minutes. Not too shabby for the old birth month.

I also acquired more books than I want to think about because it’s my party and I’ll buy books if I want to. I’ll spare you the list but you should be impressed that I still have Amazon credit left.

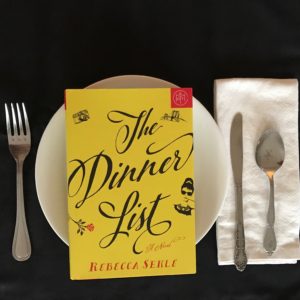

The Dinner List

The Dinner List was a Book of the Month* pick for August and comes out on September 11th. I hemmed and hawed over my box last month, trying to decide which books I wanted to get. I actually hemmed and hawed so much that other people in a BOTM Facebook group I’m in received their books and started talking about them. I try to make my BOTM picks books I think I will want to re-read since I’m making the splurge and getting them in a physical copy. The Dinner List is lighter than my usual BOTM fare and yet I’m glad I took a chance and picked it as an extra. I picked it up last weekend in the middle of two crazy weeks at work and it was exactly the distraction I needed.

The Dinner List was a Book of the Month* pick for August and comes out on September 11th. I hemmed and hawed over my box last month, trying to decide which books I wanted to get. I actually hemmed and hawed so much that other people in a BOTM Facebook group I’m in received their books and started talking about them. I try to make my BOTM picks books I think I will want to re-read since I’m making the splurge and getting them in a physical copy. The Dinner List is lighter than my usual BOTM fare and yet I’m glad I took a chance and picked it as an extra. I picked it up last weekend in the middle of two crazy weeks at work and it was exactly the distraction I needed.

The premise is fairly simple and reminiscent of an icebreaker game you were probably forced to play at summer camp–name any five people, living or dead, you’d like to have dinner with. Thus begins Sabrina’s thirtieth birthday with her best friend, Audrey Hepburn, her ex-boyfriend Tobias, and a few others. Serle does an excellent job weaving the connections to Audrey Hepburn into the book so that the choice of Ms. Hepburn at the table feels less random than it could, or the throwaway choice every girl who had A Breakfast at Tiffany’s poster on her dorm room wall would make (guilty as charged). And, as Anne Bogel noted, Audrey makes it work–she brings levity and a bit of magical whimsy to otherwise heavy moments, yet her own actual tragic history brings perspective to others.

I went into The Dinner List wanted an easy escape read and discovered a surprisingly poignant gem. The writing gave me the easy escape I wanted, the premise made the plot move fast enough to stay compelling, and the characters made me care deeply for each of them. The Dinner List probes the reasons people leave, why certain people seem drawn to our lives, and what it means to let go.

Notes

Published: September 11, 2018 by Flatiron Books (@flatiron_books)

Author: Rebecca Serle

Date read: August 25, 2018

Rating: 4 stars

Cupcake header photo credit: Audrey Fretz

*This is a referral link. I’ll get a free book if you decide to try it out. There are always deals going on for a free tote and/or free book. I’d love to chat if you want to know more, but no pressure. <3

Synopsis

Synopsis

Synopsis

Synopsis Synopsis

Synopsis