At the end of the day, all he really knew was that he was a Mexican father. And Mexican fathers made speeches. He wanted to leave her with a blessing, with beautiful words to sum up a life, but there were no words sufficient to this day. But still, he tried. “All we do, mija,” he said, “is love. Love is the answer. Nothing stops it. Not borders. Not death.”

Synopsis

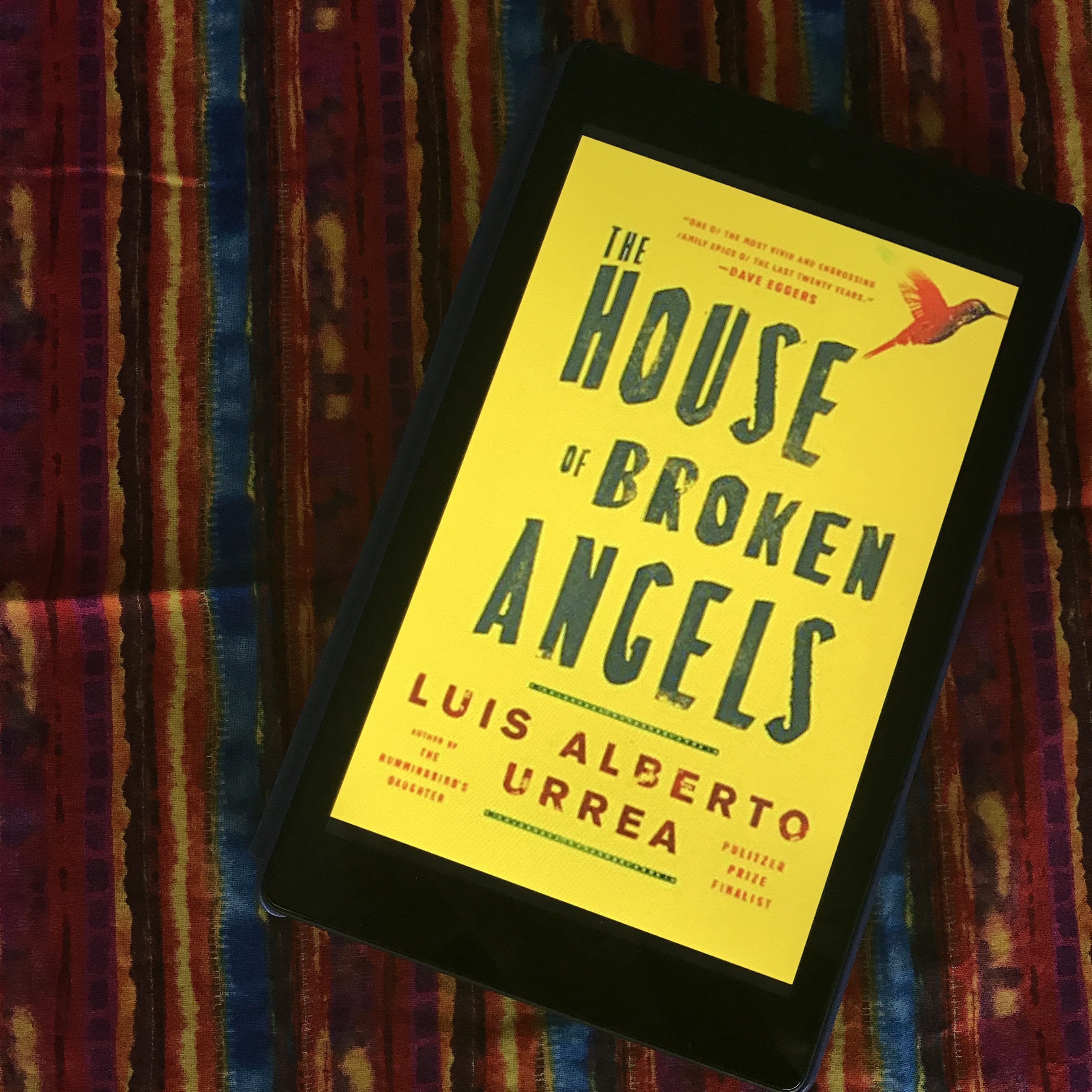

Big Angel is dying, but before he goes, he wants his family—all of the twisting branches of it—gathered for his last birthday. Nothing will derail Big Angel’s party—not borders, not internal family feuds, not even his own mother’s death. Told over the span of the days leading up to the party and the party itself, The House of Broken Angels is the story of an unforgettable Mexican-American patriarch and the life he built for his family, spanning decades and borders alike.

Prose

There is a distinctive voice to The House of Broken Angels—though I am an adult myself, Big Angel’s story is presented so intimately and warmly, I felt as if I were a child, drawn onto his knee, to hear a story from my grandfather. The prose is beautiful and enveloping in a way that invites the reader to join the family—this messy, imperfect, sprawling, grieving, celebrating family. Every word felt deliberately chosen and just right. The tone of the vignettes swing wildly from sad, to shocking, to funny, to irreverent—and yet every swing was just right.

As I read, I lost myself in this book—I wasn’t sitting in bed holding a kindle—I was in Big Angel’s backyard, smelling the food, listening to the children shriek, and waiting for Big Angel to come out of his house. For entire stretches at a time, I was in Big Angel’s world in Southern California, only to snap back after thirty or forty minutes to my quiet bedroom. Those moments when you can lose yourself so completely in a book that you are no longer aware that you are reading are so rare, and yet they became common for me on the nights I read this book.

Characters

This family is far from perfect—there’s sadness and violence waiting in the wings for many of these characters, there’s machismo and terrible choices—and yet I loved them. I loved Big Angel’s son Lalo as he grieved, as he fumbled around his definition of what it meant to be a man. I loved Little Angel (so named because Big Angel’s philandering father reused the name on his youngest son) as he sought his place within this family as the half-brother, chosen by their father over them and then ultimately abandoned as well. Minnie, dutiful daughter, yet still missing something—torn between exasperation at being treated far younger than her thirty-something years and yet wanting to stay the baby of the family if it means her father is alive to treat her that way. And Big Angel—imperfect patriarch, yet capable of such dedication to his wife and his children that he seemed larger than life, though trapped in his wasted body. These are complicated people, defined by their blood to Angel and also their humanness, their ordinariness. I half expect there to be a real De La Cruz family in San Diego throwing Big Angel his birthday this weekend.

Immigration and current events

The De La Cruz family and Big Angel himself are Mexican-Americans. They are of one place, living and contributing to the community and economy of another. Some of the members of the family, including Big Angel himself, are undocumented. And here again is where I come back to Urrea’s presentation of Big Angel as larger than life and yet so very ordinary. The House of Broken Angels is the story of the family next door, or maybe across town. You buy groceries next to Big Angel’s wife Perla and you sat next to his son Lalo in high school bio.

I noted in my last review that The Fruit of the Drunken Tree is a single story that explains why so many people might leave their homes in South American to come across our border. The House of Broken Angels is another. Immigration is never simple once actual human beings are involved. It is one thing to speak of policy and “illegals.” It is another to look a human being in the face—a veteran, a long-time employee, and favorite neighbor—and tell them they do not belong. You are not us. The stories of Big Angel’s families are not all stories of lives well-lived. Not yet. And yet they are lives of value. They are lives that belong. Books like The House of Broken Angels seem vitally important in this current climate—in a climate where it is not safe for a neighbor to confide over the fence that he is undocumented and scared. When maybe you don’t know whether you know anyone who is undocumented and it’s not really the thing you ask right now. Read books like The House of Broken Angels and Fruit of the Drunken Tree to remind yourself that what is at stake is the dignity and lives of people.

Notes

Published: March 6, 2018 by Little, Brown, & Co. (@littlebrown)

Author: Luis Alberto Urrea

Date read: July 11, 2018

Rating: 5 stars* (I swear I don’t usually give this many books 5 stars, I’ve just had a really good streak of reading).

Featured Image credit: Jonas Jacobsson

Synopsis

Synopsis You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me is an extended elegy for Lillian Alexie, mother of Sherman Alexie, award-winning Spokane-Coeur d’Alene-American author and filmmaker. Simultaneously cruel and kind, truth-teller and liar, selfish and selfless, Lillian Alexie helped form the man her son came to be, both by nurturing him and by driving him into the world away from her.

You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me is an extended elegy for Lillian Alexie, mother of Sherman Alexie, award-winning Spokane-Coeur d’Alene-American author and filmmaker. Simultaneously cruel and kind, truth-teller and liar, selfish and selfless, Lillian Alexie helped form the man her son came to be, both by nurturing him and by driving him into the world away from her.