I received a digital ARC of this book from Doubleday on NetGalley. I’m grateful to Doubleday for their generosity and am happy to post this honest review. All opinions are my own.

To die is tragic, but to go missing is to become a legend…

Synopsis

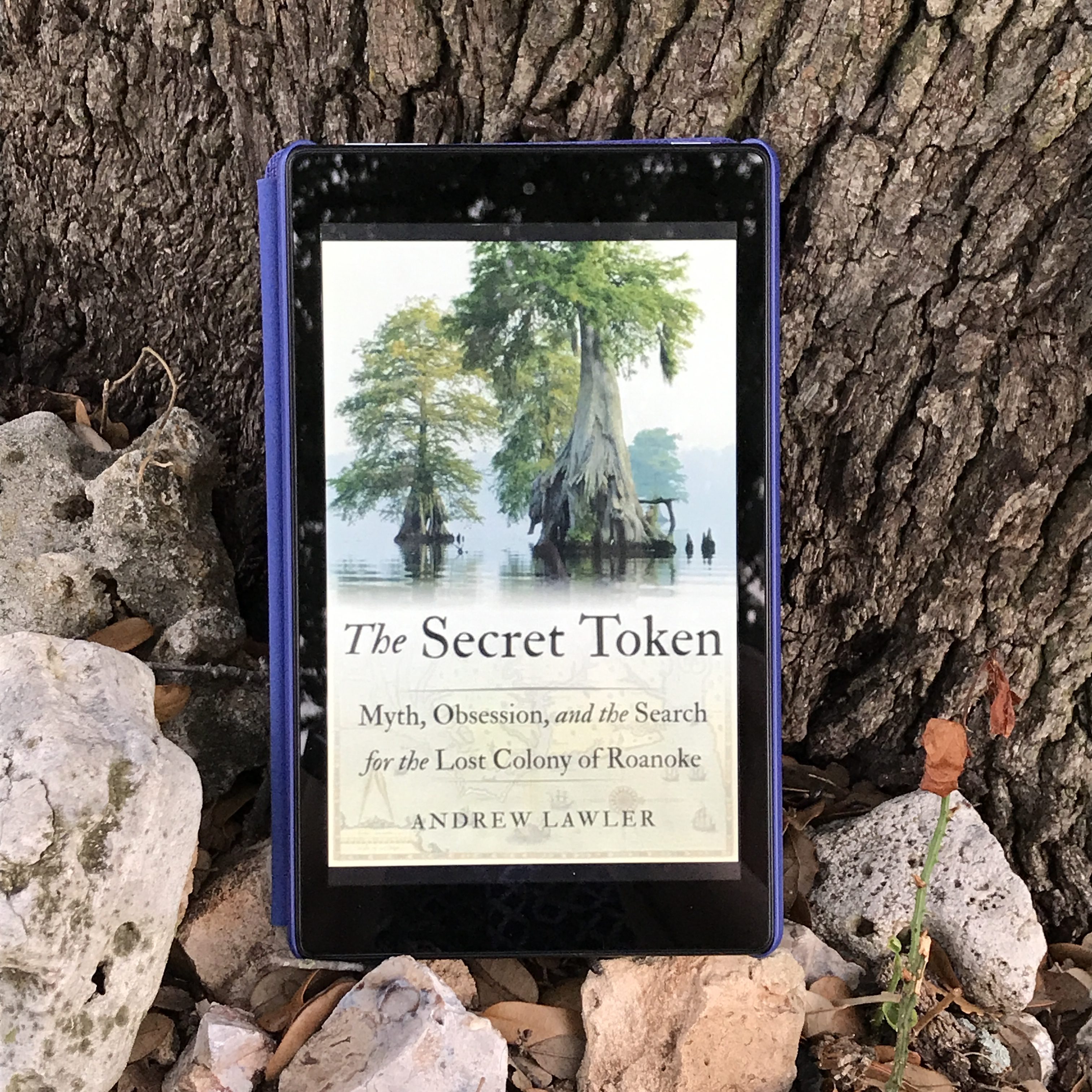

In 1587, 115 British citizens come to colonize America disappeared from Roanoke Island, leaving behind almost no traces, except for the word “Croatoan” carved into a tree. In the four hundred-plus years since, little has been discovered to explain where these men, women, and children went. To date it remains one of history’s great, unsolved mysteries. In The Secret Token, Lawler sets out the history of the colony, the search for answers, and the meaning these answers would have on the racial and cultural identity of those who trace their ancestry to the island.

Structure

Lawler structures his book in three parts that read, in many respects, like vastly different mini-books. The first section is almost purely historical narrative setting up how the colony came to be, who the major players were on the relevant voyages, the historical struggle between Spain and Britain for (essentially) world domination, and how it came to pass that the colony was lost. This section reads like a straightforward narrative history that, to be honest, almost lost me. There’s only so much history of dead white men (plus Elizabeth) that I care to read. Though, I’m pretty sure Sir Walter Raleigh’s playboy ways were left out of the history books my public schools used. (And, in Lawler’s defense, he makes this section about as interesting as it can be, given the available historical record).

If this doesn’t sound interesting to you, take heart–the next two sections have an entirely different tone and slightly fewer white men. The second section focuses entirely on the search for the colony—beginning almost immediately after their disappearance and continuing to the presently obsessed archaeologists still sifting through the North Carolina marsh silt on their weekends. The first chapters in this section on the immediate search provided the bridge that segued into the (in my opinion) more interesting searches of the modern era. While some of this remains in a narrative historical style, Lawler begins to include himself in the story. He describes interactions with historians who not only provide Lawler the relevant history but express their frustrations and theories. This section also includes some of the more eccentric characters who are still out there searching. Their inclusion shows the hold the mystery of the colony still has on people, making the book feel relevant and a little bit tantalizingly voyeuristic. As Lawler is sucked deeper into the subject matter of his own book, his writing takes on hints of the obsession that infects many of those he’s interviewing and invites the reader along for this ride. In this vein, Lawler leaves no stone unturned—evaluating each archaeological and cartographic find, including the controversial (and possibly faked) Dare Stone.

The last section, and the reason this book earned my 3 ¾ stars, looks at the myth through the lens of race. One of the reasons this myth still holds such sway is that what ultimately happened to the Colony and to baby Virginia Dare—the first white child born in America—has lasting implications to both those who cling to white supremacy and those who claim first nation heritage in this part of the country. Within this section, Lawler also discusses how the area came to be home to many African slaves and their descendants, making this area of mixing bowl of races. When the government sought to maintain white supremacy, the Native American descendants were successfully pitted against their African neighbors in a bid to create a racial hierarchy that preserved white supremacy.

Race and Identity

My grandmother was born in North Carolina, one of twelve children and the eldest girl. Her name was Virginia Dare Moore. When I learned in elementary school that the first child born in the colonies was named Virginia Dare, I thought this was the coolest. Until very recently, when I thought about possible kid names (not pregnant, not trying), I thought about naming a girl after my beloved Nana. My dad had mentioned in passing on an occasion that my grandmother always hated her name and I never knew why. After reading this book, I suspect I know.

Beginning in the 1800s and particularly at the turn of the 20th Century, Virginia Dare was adopted as a white supremacist icon. One of the most likely possibilities of what happened to the colony is that it was absorbed into the local native population—there are no remains that suggest they died on the island (by natural or other means) and they did leave behind the word Croatoan (the name of a local tribe/area) carved in a tree. The problem with this answer to the Roanoke mystery if you’re a racist white woman who wants the vote but wants to maintain the white status quo, is that it necessarily means that white women mixed with native men (and vice versa) and had mixed race children. Enter virginal Virginia Dare who lived with the natives because she had no other choice to survive but stayed apart, a shining, white example completely without historical basis in fact.

On the other side, the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina is, to the best of anyone’s knowledge, the possible ancestors of the tribes who once lived on and around Roanoke Island. If the colonizers mixed with any tribe, their descendants may be members of the Lumbee Tribe. This tribe, while recognized by the state, is not formally recognized by the federal government, which means they are denied many of the benefits afforded to officially “recognized” Native American tribes. One possible method to solve the mystery would be to trace lineages of the White family in Britain (Virginia Dare’s grandfather) and compare the genes of those identified descendants to those in the Lumbee tribe. Many members of the Lumbee (and many Native Americans period), however, have resisted this suggestion. For some, there is the real fear that the information gathered would be misused (a belief well-supported by how our government has historically treated first nation peoples as well as the story of Henrietta Lacks). For others, there is a question of what it would reveal. A handful of Lumbee who have agreed to participate have discovered that their genetic markers indicate they are majority white and have significant African-American ancestry as well. For those in the community whose identity is defined by being Lumbee, by having native ancestors, these tests have the ability to call everything they know about themselves into question.

The myth of the Lost Colony of Roanoke is not then, just a straight-forward question of what happened to 115 people in 1587. Rather, the myth extends to the convenient and often false narratives we still tell ourselves about who is “pure,” who belongs, and who we are.

Recommended

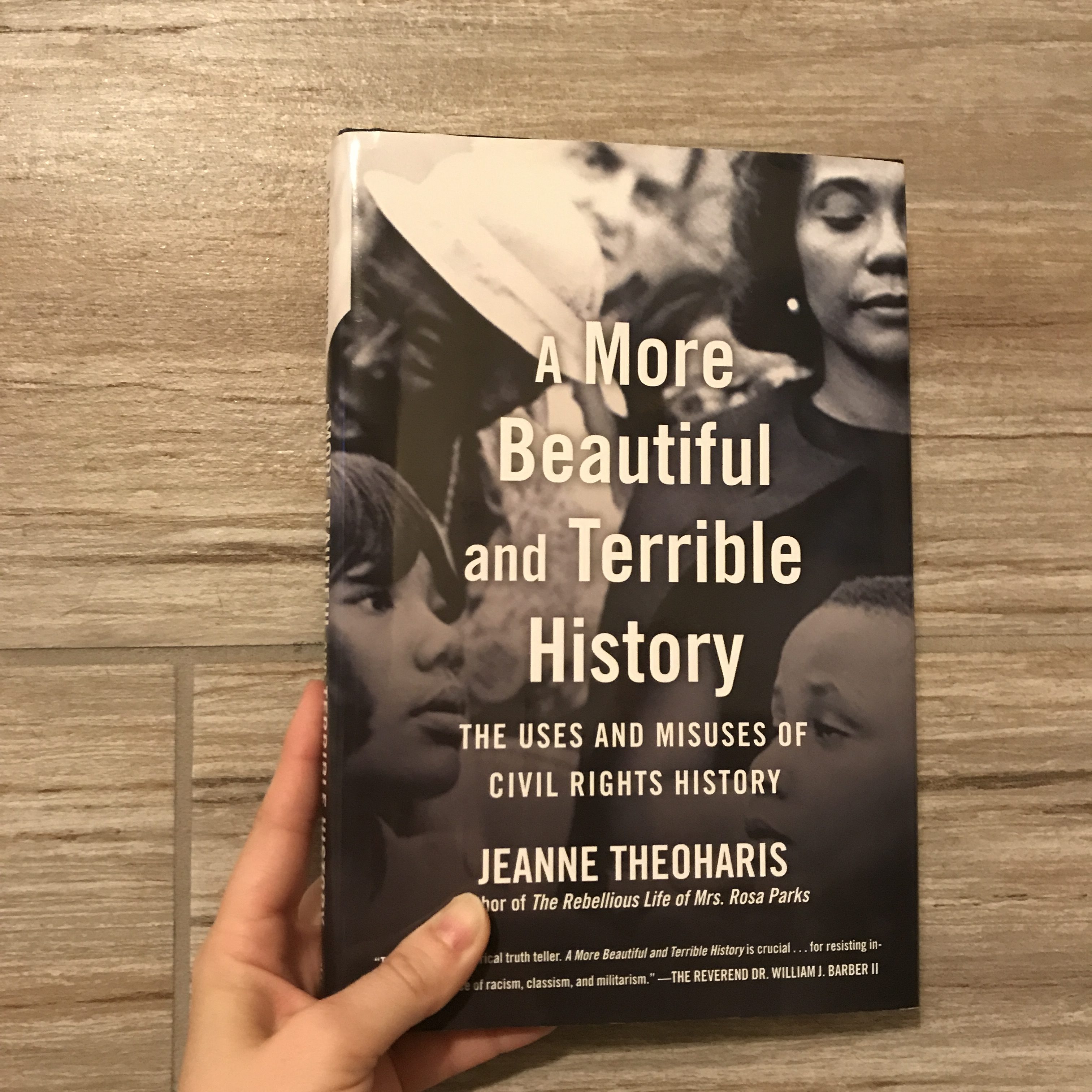

As a Virginian with North Carolinian roots, I grew up hearing about the Lost Colony of Roanoke and thought it was fascinating. I was never told and never realized the significance the still mystery has to people today or the racial underpinnings of the theories. The Secret Token is a book that will stick with me for a while—much like A More Beautiful and Terrible History, it calls into question the history I learned as a child and the motives of the creators of our national history and myths.

Notes

Published: June 5, 2018 by Doubleday (@doubledaybooks)

Author: Andrew Lawler

Date read: May 30, 2018

Rating: 3 ¾ stars

Conflict

Conflict

First, Newport defines “Deep Work” as “professional activities performed in a state of distraction free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.” Shallow Work is, essentially, everything else—it is the easily replicable things that suck time not brainpower but do not contribute significantly to the furtherance of any goals. What follows after this set up is a series of rules/proposals/examples that show why arranging your time and focus to provide solid blocks of time for Deep Work is vital to maximizing your working potential.

First, Newport defines “Deep Work” as “professional activities performed in a state of distraction free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.” Shallow Work is, essentially, everything else—it is the easily replicable things that suck time not brainpower but do not contribute significantly to the furtherance of any goals. What follows after this set up is a series of rules/proposals/examples that show why arranging your time and focus to provide solid blocks of time for Deep Work is vital to maximizing your working potential. Another issue I had with this read that contributed to the running-together-problem was that there was almost no context given for who the person was that was being described. Sure, some (like Freud or Benjamin Franklin) didn’t need an introduction, but the guy who I think I figured out was a Russian choreographer definitely did. Even if I’d heard a name before, I couldn’t tell you why I knew them or what their body of work was. Not recognizing the subject of the essay contributed to the disconnect and kept me in skim-only mode.

Another issue I had with this read that contributed to the running-together-problem was that there was almost no context given for who the person was that was being described. Sure, some (like Freud or Benjamin Franklin) didn’t need an introduction, but the guy who I think I figured out was a Russian choreographer definitely did. Even if I’d heard a name before, I couldn’t tell you why I knew them or what their body of work was. Not recognizing the subject of the essay contributed to the disconnect and kept me in skim-only mode.

Synopsis

Synopsis You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me is an extended elegy for Lillian Alexie, mother of Sherman Alexie, award-winning Spokane-Coeur d’Alene-American author and filmmaker. Simultaneously cruel and kind, truth-teller and liar, selfish and selfless, Lillian Alexie helped form the man her son came to be, both by nurturing him and by driving him into the world away from her.

You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me is an extended elegy for Lillian Alexie, mother of Sherman Alexie, award-winning Spokane-Coeur d’Alene-American author and filmmaker. Simultaneously cruel and kind, truth-teller and liar, selfish and selfless, Lillian Alexie helped form the man her son came to be, both by nurturing him and by driving him into the world away from her.

Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing

Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing