Freshwater is going to be one of those books that draws a strong reaction from people—the viewpoint is non-standard, the structure unusual, and the content will be blasphemous for some. I adored it.

Synopsis

Synopsis

As a side note, I often write the synopsis last and usually struggle. It’s not my favorite part of this process but I assume people want at least a basic plot summary at the beginning. I have never struggled this much to summarize a book in a way that does it justice.

Freshwater is ultimately the story of Ada, beginning with her time as an embryo when she is first inhabited by the Ogbanje* spirits that will come to define her life. We follow Ada from birth through young adulthood, experiencing her life as it is described largely by the Ogbanje themselves. Her life is never easy—constantly at the whims of the spirits that embody her—and yet, perhaps because she is so full of spirits, her life has been more full than that experienced by others.

Viewpoints

I don’t even have a mouth to tell this story. I’m so tired most of the time. Besides, whatever they say will be the truest version of it, since they are the truest version of me….In many ways, you see, I am not even real. –Ada

She named me this name, Asughara, complete with that gritty slide of the throat halfway through. I hope it scrapes your mouth bloody to say it. When you name something, it comes into existence—did you know that? -Asughara

Freshwater is told in alternating viewpoints, though the viewpoints don’t share equal time, nor do they alternate in any particular order. The majority of the story is told from the viewpoint of the simmering, unnamed We—constantly in motion, constantly swirling around in Ada. She is subject to their whims in the sense that she can be querulous and divided in her attentions and wants. They are not of this world and they embody Ada such that she isn’t entirely either. The We open the book, describing Ada’s childhood in Nigeria as a middle child with a physically absent mother and an emotionally absent father. They return periodically, the Greek chorus filling in the audience, if the Greek chorus were the inner workings of a major character’s mind.

When Ada leaves Nigeria for college in the United States, she is shortly beset upon by one of the Ogbanje that becomes dominant enough to earn a name—Asughara.* Asughara is blood-thirsty and bent on destruction—others mostly, though her actions while embodying Ada will drive Ada to her limit. She is almost solely self-centered (Asughara-centered over Ada-centered) at the cost of all others, though she also protects Ada in some ways from experiencing violence, particularly sexual violence.

Very, very rarely Ada herself does speak, giving the reader the sense (mostly) of the agony of being beset upon by these gods, constantly at their mercy, constantly pulled in different directions that ultimately seem only to point to her destruction—a destruction that will free the Ogbanje back to the brothersisters.

There is one other viewpoint that is dominant enough to be named but does not, that I can recall, have any chapters directly from his viewpoint. When Asughara wanes, her opposite is St. Vincent. A male Ogbanje striking for his gentleness and yet no less fully encompassing of Ada’s self than Asughara.

Trigger Warning / Cautions

There are setting events that cause some of Ada’s Ogbanje/personalities to become dominant at different points in time. As you might expect, one of these things is a rape—while it is not described in excessive detail, its impact on Ada is and so this deserves a trigger warning. There are also a series of unhealthy relationships that at times include some elements of physical violence that may make some readers uncomfortable. This is something that I usually prefer to avoid; however, because the viewpoints describe the actions happening to Ada in a removed sense, these weren’t as triggering to me personally as they could have been—i.e. Ada doesn’t describe the violence to her body, Ashughara or the We/Ogbanje chorus do at a level removed. The removal itself indicates Ada’s own detachment from the trauma but in some ways, this device also made it easier for me to read.

While not something that deserves a trigger warning in the usual sense of the phrase, when St. Vincent embodies Ada, he doesn’t feel at home in her feminine body such that she starts wearing a binder and even has reduction surgery to be more masculine or, at least, more androgynous. I am not versed in the best ways to sensitively approach this topic. While Emezi seems to use it to show how Ada was at the mercy of the competing whims of the Ogbanje, I can also see the idea that her “trans personality” (for lack of another way to name it) is the result of some whim of the gods being an offensive way to explain why someone might not feel at home in their body—it isn’t Ada that wants to be more masculine but rather St. Vincent when he is forefront among the Ogbanje.

Writing

The writing—the word choice, cadence, and sentence structure—is loosely narrative in a sprawling, serpentine sense. This isn’t a Faulknerian stream of consciousness structure, but this is also not straight narrative. The spirits speak as they want and they rarely want to report what is directly happening. You have to read between the lines of what the Ogbanje describe they are doing to understand what this means for Ada—what this manifestation means for her body as it moves through the world. The writing felt fresh and original, never overdone for me, though it will absolutely drive away some readers. I would encourage you, dear reader, to push through several chapters before you give up on this one if it doesn’t seem immediately for you. Because the writing is so unlike most of what is readily out there for Western audiences to easily consume, it can take a few chapters to settle into the way the Ogbanje narrate but the investment is worth it. If the topics aren’t for you then that’s not something I can likely change but I propose that the writing is something you can get used to and this book is worth the investment, particularly if reading diversely is something you value.

Blasphemy

Jesus—the god of the white man—is presented as essentially another Ogbanje. He isn’t truly in the sense that he isn’t African and the Ogbanje are the Igbo spirits; however, he interacts with Ada in much the same way as the other spirits. He rarely answers Ada when she seeks his help and he is no more holy and no more a god than the others. If this is going to bother you, this isn’t a book you should start.

Mental Illness

We’ve wondered in the years since then what she would have been without us, if she would have still gone mad. What if we had stayed asleep? What if she had remained locked in those years when she belonged to herself?….The first madness was that we were born, that they stuffed a god into a bag of skin. -We

Inaccurate and/or lazy descriptions of mental illness are something I can’t abide in a book and yet…I had no problem with Freshwater. The manifestation of the Ogbanje through Ada is pretty clearly interpreted by people around Ada as the manifestation of mental illness—she dissociates into the various personalities, she can be manically hedonistic when in Asughara’s hands and is self-harming to the point of a suicide attempt.

On the one hand, the idea that mental illness is caused by the possession of evil spirits is an offensive proposition. And yet, I don’t think Emezi’s point was that Ogbanje are the source of all mental illness. Rather, while the outside word might interpret Ada’s actions as those of someone with mental illness, she isn’t one. Her actions have another cause but this doesn’t mean that all individuals with mental illness are also at the mercy of the Ogbanje. Because Emezi doesn’t present the Ogbanje as a universal experience outside of the Igbo people, I didn’t read Freshwater as really being a book about mental illness at all. Rather, mental illness was the periphery, an explanation others had for Ada but not the explanation for her at all.

Stay With Me

Shortly before I read Freshwater, I read Adebayo’s Stay With Me. Adebayo is also Nigerian (Emezi grew up in Nigeria and is Igbo, one of the larger people groups found in Nigeria). In Stay With Me one of the beliefs that the characters discuss is the idea that malevolent spirits can be born to a mother, only to die and then repeat this cycle. In order to prevent the malevolent spirit from returning—so that, in essence, a real child can be born to the mother—the body the malevolent spirit inhabited must be mutilated and the object they use as their tether to this world and this family must be found and destroyed. I don’t recall Adebayo using the word Ogbanje (I could definitely be wrong) but these are the same spirits that embody Ada in Freshwater, except the spirits in Freshwater didn’t cause Ada to die as a child. Where Stay With Me peripherally explains what the Ogbanje often cause, Freshwater explains what happens when they stay and the havoc they can wreck. If you read Freshwater and enjoy it, you may enjoy Stay With Me. If you enjoyed Stay With Me and are wiling to go a step further down the path into the beliefs espoused by some of the minor characters in Stay With Me, then check out Freshwater.

Notes

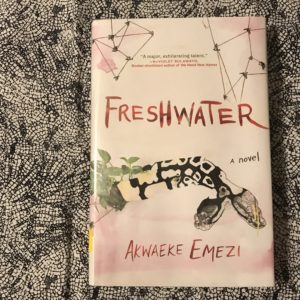

Published: February 13, 2018 by Grove Atlantic (@groveatlantic)

Author: Akwaeke Emezi (@azemezi)

Date read: March 8, 2018

Rating: 4 ¼ stars

*While the Microsoft Word symbols have a plethora of symbols/letters for other languages, the “O” in Ogbanje and the “u” in Asughara actually have a dot under them in (what I believe is) Igbo based on the Author’s dual ethnicity as Igbo and Tamil. Word, not terribly surprisingly, doesn’t have this symbol.