I think I did believe that love had immense power to unearth all that was good in us, refine us, and reveal to us the better version of ourselves. And though I knew Akin had played me for a fool, for a while I still believed that he loved me and that the only thing left for him to do was the right thing, the good thing. I thought it was a matter of time before he would look me in the eye and apologise.

So, I waited for him to come to me.

Delinquent (Oops?)

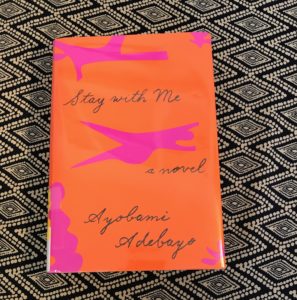

I’m not sure I’ve been quite so delinquent on posting a book that had a sort-of-deadline built into its relevance but here we go. I read the MARCH book club selection for the Modern Mrs. Darcy book club and finished timely (March 4th!) and yet haven’t felt like I’ve had a chance to really sit down and process everything that is this book.

Synopsis

Stay With Me follows Yejide, a Nigerian woman who has been unable to have a child with her husband Akin. The story follows Yejide as she takes increasingly desperate steps to have and then keep a child.

Avoiding the Spoilers

It is hard to discuss this book without spoiling the events. This was a book I experienced with no extra information besides what appeared on the flap-copy. I didn’t know what exactly Yejide and Akin were willing to try or how each of those steps would result. This will be a short review—I want to review it because it is so well done but do not want to spoil any of the little events in the middle along the way. So I apologize now for my brevity and vaguess—do not let this deter you from reading but rather take it as a sign that you should pick up the book and see for yourself why I am rating it so highly.

Loss

The most prominent and obvious theme in Stay With Me is one of loss. There is the loss of children—each loss different in its means and impact—but also the loss of relationship and self. As is common in couples who experience this kind of loss, with each step Yejide and Akin take to have a keep their children, the two are driven further apart. Steps taken to have the child that will ultimately strengthen their marriage become the wedges between them. With each loss, Yejide also loses parts of herself. A chipping away so subtle that it isn’t clear until whole sections have been sheered off that this was happening. At a apex in the plot, Yejide makes a choice to initiate the loss herself—when you have had what you love most repeatedly wrenched from you hands, at some point initiating the coming loss feels like the only way to protect yourself, to try to keep a shred of agency. I am not sure I have ever read another book that explores the myriad facets of loss and its impacts so effectively.

Structure

The book does jump around a bit in time and narrator—the bulk of the story-telling is from Yejide’s point of view, though every third or fourth chapter is Akin. The chapters are not labeled so the reader has to realize the narrator has changed—this was somewhat disconcerting at times, though it was easy enough to realize this had happened within a few sentences. It didn’t bother me and it seemed a deliberate choice made by Adebayo to deliberately disrupt the narrative and leave the reader feeling as disrupted and off-balance as Yejide and Akin. The abrupt narration change did, however, both some readers—the handful of negative reviews on Amazon mention this. The time jumps are labeled, so while they are also abrupt at times, it is clear you’ve moved forward or backwards in time. This kind of structure almost never bothers me—I like non-standard devices and techniques and I like to see authors play with things like this. This is, however, something it keep in mind if this style is something that usually impacts your ability to connect with a book.

Characters

To me, Yejide was a likeable narrator, drawing me in. Though we have nothing in common on paper—I have never even been to Nigeria, I have never tried to have a child—her experiences and the way Adebayo has her narrator speak to the reader made me feel a connection to her. She is well fleshed out—flawed but in ways that make sense for her experiences. She makes terrible choices at times, but by the time these happened, I connected with her so deeply I understood why she made the choice and was making it along with her. Stay With Me is a fascinating character study and makes me want to read more of Adelbayo’s work.

Because Yejide is the main narrator, I had a biased view of Akin. I felt affection for him early, as he supported Yejide. But as he and Yejide few further apart, I came to pity him, to see him as weak. Here again, this speaks to the power of Adebayo’s narrator. Stay With Me manages to simultaneously present Akin in the way his wife sees him, to have her thoughts color his presentation; yet just enough of his own character shines through here and there in his chapters that you still see him as a fleshed out person. He isn’t merely a foil or a plot device for Yejide’s development. He is his own character and I enjoyed digging for his real personality under Yejide’s assumptions about his motives.

In the discussion Anne hosted with Adebayo for book club, it came up that some people found all of the characters unlikeable and they struggled to finish. I was surprised by this assessment—Yejide and Akin seemed like people to me. Real people are not always likeable. And perpetually likeable characters are boring. Adebayo introduced both Yejide and Akin so thoroughly that I understood why they were making the choices they made; I understood why they were hurt and thus why they hurt others. I didn’t find either of them irredeemable or so distasteful that I wanted to stop reading.

The other fun little note that come up during the discussion is that all Yoruba names mean some thing. For Yejide, anyone who met her would know someone died before she was born—they would assume her grandmother but in Yejide’s case it was actually her mother who died giving birth to Yejide. Akin’s name means a courageous man—an ironic touch the more you get to know him.

Highly Recommended

I feel again that I need to apologize for being so vague—I feel like I’m saying “You should read this book but I can’t tell you why! You just should!” Obvious triggers surrounding child loss notwithstanding, this is a book I highly recommend if you like character-driven books. There are also sufficient events to keep the book moving, with moments of crisis, so even those who need more heavily plot-driven books will find something here to keep them reading. The entirety of the action occurs in Nigeria and Adebayo is herself Nigerian (I believe she said she was Yoruba), making this a book for both #diversebooks and #ownvoies.

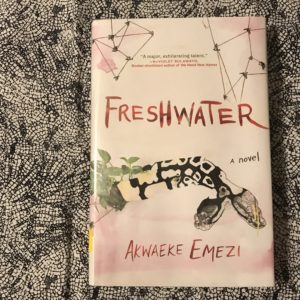

Flight Pick — Americanah and the value of listening to books by foreign writers

Anne’s flight pick to read with Stay With Me was Chimamanda Adiche’s Americanah. I actually “read” (listened) to Americanah early in 2017 so I didn’t revisit it last month. I felt like listening to Americanah last year was particularly helpful—there is a cadence to the writing that was accessible to me as a white American reader that wasn’t available if I had only read the book. Indeed, having listening to Americanah I felt like I could read Stay With Me and even Freshwater better—the speech and cadence of the Nigerian English stuck with me and aided my reading. If you haven’t ever listened to an audiobook of a Nigerian writer, I recommend your first book be one you listen to—it will make the experience of that book and subsequent books richer.

Notes

Published: August 22, 2017 by Knopf

Author: Ayobami Adebayo

Date read: March 4, 2018

Rating: 4 ½ stars

Featured Photo Credit: Alexis Brown

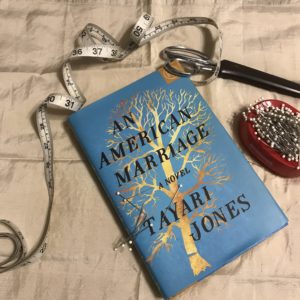

Synopsis

Synopsis All around Roy were shards of a broken life, not merely a broken heart. Yet who could deny that I was the only one who could mend him, if he could be healed at all? Women’s work is never easy, never clean.

All around Roy were shards of a broken life, not merely a broken heart. Yet who could deny that I was the only one who could mend him, if he could be healed at all? Women’s work is never easy, never clean.