One of the things I have tried to do with my reading over the last year or so is to read diverse voices, particularly diverse non-fiction. I don’t want to only read books where I already agree with everything the author proposes, nor do I want to put a book down solely because it makes me uncomfortable where the thing that is making me uncomfortable is a person of color talking about their own experience. (Books like My Absolute Darling where a white man uses the c-word too much, however, are perfect examples of when I should put a book down just because it makes me uncomfortable). With that in mind, I recently finished three books by Black authors—We Were Eight Years in Power by journalist/author Ta-Nehisi Coates, When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir by Patrisse Khan-Cullors, and This Will Be My Undoing by essayist Morgan Jerkins. I am not going to pretend that as a white woman I am qualified to “review” them, instead what I hope to achieve here is a summary of each so that you can decide if these are books that would challenge you and your privilege if you read them as well. All three are valuable recent books.

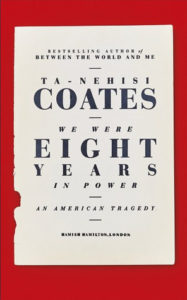

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy

Coates’s most recent offering is a compilation of the essays he wrote for The Atlantic during the eight years of Obama’s presidency, one per year, with commentary of what was going on in his life and the life of many black Americans during each of the eight years. Because the essays were originally magazine articles, there is some repetition among them of certain points or common phrases that, if this were a book of essays, would likely have been edited to fit better. None of the thoughts or arguments that were repeated were long, so the repetition didn’t bother me as a reader, nor did it cause me to go into skim mode. It was just noticeable. The introductions to each article were interesting in that, while the context was helpful, Coates also comments on the following article—things he wished he had done differently, whether some of his points or predictions held up, and general criticism of his work. As a reader, this was a strange device and it made me wish that the “intro” essays followed the pieces instead. His critique of his own work colored how I read the article and I wished before some of them that I had a chance to form my opinion before reading his hindsight-critique.

Coates’s most recent offering is a compilation of the essays he wrote for The Atlantic during the eight years of Obama’s presidency, one per year, with commentary of what was going on in his life and the life of many black Americans during each of the eight years. Because the essays were originally magazine articles, there is some repetition among them of certain points or common phrases that, if this were a book of essays, would likely have been edited to fit better. None of the thoughts or arguments that were repeated were long, so the repetition didn’t bother me as a reader, nor did it cause me to go into skim mode. It was just noticeable. The introductions to each article were interesting in that, while the context was helpful, Coates also comments on the following article—things he wished he had done differently, whether some of his points or predictions held up, and general criticism of his work. As a reader, this was a strange device and it made me wish that the “intro” essays followed the pieces instead. His critique of his own work colored how I read the article and I wished before some of them that I had a chance to form my opinion before reading his hindsight-critique.

Though I read this book weeks ago, two of the essays in particular have stuck with me. The first and one that I didn’t expect to agree with as much as I ultimately did was his article on the Case for Reparations. I grew up in a conservative household and, until relatively recently, regurgitated arguments I’d heard growing up about the evils of affirmative action. For someone who grew up thinking affirmative action was a bad idea, reparations are essentially anathema. While I’ve come around on affirmative action, admittedly my thoughts on reparations before reading this article were generally along the lines of—we probably do owe them something but it would be impossible so why are we spending time on this? The Case for Reparations set out a history I was unfamiliar with, including the history of systemic discrimination on the part of the US government to prevent African Americans home ownership while enabling white families to purchase homes. Where homes are the most common source of wealth and wealth-building in this county, this set African Americans back generations. I found myself convinced by the end of Coates’s argument that, at a minimum, we need to actually study the feasibility of determining what is owed to whom and how that could be brought about.

The other essay that stuck with me was one I remember skimming in parts when I came out in The Atlantic but didn’t read in its entirety until this book. The Black Family In the Age of Mass Incarceration set out a history of how we find ourselves with the largest incarcerated population of any first world country, with vastly disproportionate rates of incarceration between whites and blacks with the same backgrounds. I assumed that the article was going to make a similar argument as Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. Coates’s argument, however, doesn’t go quite as far as Alexander’s. As with reparations, he does explain how government policies created disparate treatment between the two races that resulted in higher rates of incarceration of blacks and he explains how the current paid prison system only serves to reinforce the high rates of incarceration. (In a nutshell—when prison becomes a business, bodies become the commodities that must be obtained at high rates to keep the business open. And the bodies that draw the least criticism to consume are Black bodies.)

While many of the articles are still available online, there was a power in reading them together with Coates’s thoughts on each year of the Obama presidency, including critique of Obama’s failure to do more for African Americans who won him the presidency and the respectability politics he seemed unwilling to depart from. In some ways, the most powerful essay in the book was the prologue, written after the “black-lash” against the second Obama term that resulted in the election of what Coates calls the First White President. The compilation of all of these articles together along with the essays that introduce them and close the book, make it worth getting a copy of the book and not just re-reading the articles online. This was one of a handful of books that before I’d even finished my library copy, I’d ordered my own to keep.

Notes

Published: October 3, 2017 by One World

Author: Ta-Nehisi Coates

Date read: February 18, 2018

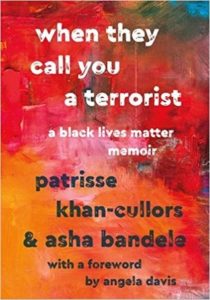

When They Call You A Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir

The focus of probably the first half of When They Call You a Terrorist was not what I expected since Khan-Cullors’s recollections seemed more about her brother’s experience with an inadequate public and prison mental health system than it did on her brother’s blackness. Which is not to say that his blackness was ignored or even that his blackness didn’t greatly affect the way the mental health and law enforcement systems responded to him. I simply didn’t know much about Khan-Cullors before listening (I think literally the only thing I could recall hearing about was her partner’s being detained trying to come into the country from Canada) and so did not expect the lengthy discussion of mental illness. Her compassion for her brother and the way the family tried to treat him and have others treat him with as little force as possible made me hurt for her. (Khan-Cullors reads the book herself, which added to the tragedy inherent in many of the sections.) Because so much of the first half of the book is simultaneously a study of being black and having a mental illness, I would go so far as to say that if you’re interested in hearing about the lived experience of trying to obtain mental health care in a broken system, this is a powerful book for that alone.

The focus of probably the first half of When They Call You a Terrorist was not what I expected since Khan-Cullors’s recollections seemed more about her brother’s experience with an inadequate public and prison mental health system than it did on her brother’s blackness. Which is not to say that his blackness was ignored or even that his blackness didn’t greatly affect the way the mental health and law enforcement systems responded to him. I simply didn’t know much about Khan-Cullors before listening (I think literally the only thing I could recall hearing about was her partner’s being detained trying to come into the country from Canada) and so did not expect the lengthy discussion of mental illness. Her compassion for her brother and the way the family tried to treat him and have others treat him with as little force as possible made me hurt for her. (Khan-Cullors reads the book herself, which added to the tragedy inherent in many of the sections.) Because so much of the first half of the book is simultaneously a study of being black and having a mental illness, I would go so far as to say that if you’re interested in hearing about the lived experience of trying to obtain mental health care in a broken system, this is a powerful book for that alone.

Khan-Cullors lived experience was about as diametrically opposed to mine as possible, with the idea of “organizing” being something I don’t think I had heard of in any real sense before Obama came along (and then probably in a discussion of how he wasn’t “qualified” since that was all he had done). In contrast to my privileged and sheltered life, Khan-Cullors was reared in an atmosphere of social organizing, going to a school that focused on social justice issues, and having a diverse group of friends—both racially and on the gender spectrum.

I have literally nothing negative to say about this book because it is her lived experience and, unlike say J.D. Vance, she doesn’t use random anecdotes from her life to cast aspersions on an entire group of people. Khan-Cullors sticks pretty closely to her own story and, in doing so, comes across as credible—one can disagree with her politics but you can’t argue that this was her life. The audiobook features a short interview with Khan-Cullors after the book where she says that one of her goals was to write a “truth-telling, healing-justice” story. She succeeded.

Notes

Published: January 16, 2018 by St. Martin’s Press

Author: Patrice Khan-Cullors & Asha Bandele

Date read: March 8, 2018

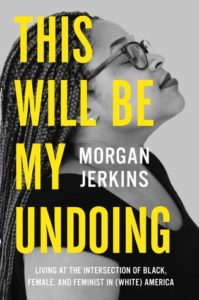

This Will Be My Undoing: Living At the Intersection of Black, Female, and Feminist in (White) America

Admittedly, of the three books featured here, this one probably made me the most uncomfortable, but mostly because I don’t read very many books that prominently feature essays about labia and vibrators. Which, let me quickly add, were not mentioned for shock value—this wasn’t a book that I felt like I wanted to put down because it veered into the gross-Lena-Dunham-esque territory. There were just a few moments of “oh—I don’t know that I’d talk about that publicly but here we go.” I will say, this book probably made me the most uncomfortable of the three, though it was an uncomfortable that, like Hunger, was probably good for me to sit with.

Admittedly, of the three books featured here, this one probably made me the most uncomfortable, but mostly because I don’t read very many books that prominently feature essays about labia and vibrators. Which, let me quickly add, were not mentioned for shock value—this wasn’t a book that I felt like I wanted to put down because it veered into the gross-Lena-Dunham-esque territory. There were just a few moments of “oh—I don’t know that I’d talk about that publicly but here we go.” I will say, this book probably made me the most uncomfortable of the three, though it was an uncomfortable that, like Hunger, was probably good for me to sit with.

Jerkins book is, like Coates, a series of essays—this was a bit of a mixed-bag for me. Each essay stood alone which made the audiobook easier to put down and pick back up but it also meant the stories jumped around in time a bit. The vision I had of Jerkins and her experience at one point in the book was changed when she revealed some piece of her early upbringing in a later essay. I wouldn’t call this book a favorite but it is a book I’m absolutely glad that I read—as I mentioned before, I want to push the boundaries of what I find comfortable and I want to specifically read more memoirs and essays from people of color about what it is like to have lived in their shoes—as Jerkins says, at the intersection of Black, Female, and Feminist in White America. I recommend this book specifically because it did make me uncomfortable and because Jerkins’s voice is like none other I’ve heard. For someone so young (oh god, the authors are starting to be younger than I am!), she has a powerful voice and I look forward to seeing what is to come from her.

Notes

Published: January 20, 2018 by Harper Perennial

Author: Morgan Jerkins

Date read: March 19, 2018

Header photo credit: Daniel Garcia

If I tell you what happened that night in Ekaterinburg I will have to unwind my memory—all the twisted coils—and lay it in your palm. It will be the gift and the curse I bestow upon you. A confession for which you may never forgive me. Are you ready for that? Can you hold this truth in your hand and not crush it like the rest of them?…But, like so many others through the years, you have asked:

If I tell you what happened that night in Ekaterinburg I will have to unwind my memory—all the twisted coils—and lay it in your palm. It will be the gift and the curse I bestow upon you. A confession for which you may never forgive me. Are you ready for that? Can you hold this truth in your hand and not crush it like the rest of them?…But, like so many others through the years, you have asked: Synopsis

Synopsis Synopsis

Synopsis

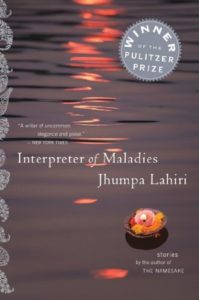

When Anne Bogel chose Interpreter of Maladies as her flight pick for This Must Be The Place, I was pleased. I’ve owned this book and hadn’t had a chance to read it yet (#storyofmylife) and really enjoyed The Namesake when I read it several years ago. I’m glad I read Interpreter of Maladies, though I didn’t love it as much as I wanted to.

When Anne Bogel chose Interpreter of Maladies as her flight pick for This Must Be The Place, I was pleased. I’ve owned this book and hadn’t had a chance to read it yet (#storyofmylife) and really enjoyed The Namesake when I read it several years ago. I’m glad I read Interpreter of Maladies, though I didn’t love it as much as I wanted to.

Hunger is Roxane Gay’s most recent work—a series of essays of varying lengths about food, her body, and hunger—for what she can and can’t have. Unlike Bad Feminist, Gay reads Hunger herself—an addition that made the audiobook more powerful than the text alone and why I went ahead and used the Audible credit. This is a book I think I will need to revisit a few times to really experience Gay’s writing and argument, largely because of the power and nuance here. I don’t want to assume I got everything out of this book the first time.

Hunger is Roxane Gay’s most recent work—a series of essays of varying lengths about food, her body, and hunger—for what she can and can’t have. Unlike Bad Feminist, Gay reads Hunger herself—an addition that made the audiobook more powerful than the text alone and why I went ahead and used the Audible credit. This is a book I think I will need to revisit a few times to really experience Gay’s writing and argument, largely because of the power and nuance here. I don’t want to assume I got everything out of this book the first time. The other book I read but didn’t plan to fully review this month was Claire Messud’s The Burning Girl. The Burning Girl is the story of childhood best-friends Julia and Cassie in the years between late middle school and early high school or, rather, it’s the story of how Julia and Cassie fall apart. Of how growing up can often be the fracturing of the “forever” you thought as an essential and automatic part of the BFF moniker.

The other book I read but didn’t plan to fully review this month was Claire Messud’s The Burning Girl. The Burning Girl is the story of childhood best-friends Julia and Cassie in the years between late middle school and early high school or, rather, it’s the story of how Julia and Cassie fall apart. Of how growing up can often be the fracturing of the “forever” you thought as an essential and automatic part of the BFF moniker. ’ve picked another ten books for March, though a bunch of books I was excited about came in at the library so I’m just barely paying lip service to #theunreadshelfproject this month. I have already finished Stay With Me (MMD March pick) and Force of Nature, the second Aaron Falk mystery from Jane Harper and its only the fifth, so the month is starting off strong. I also hope to finish Freshwater, Lab Girl (DBC), My Life On the Road (audio), I Was Anastasia, Priestdaddy, Oliver Loving, and The Hazel Wood. Of those, I own only My Life On the Road, I Was Anastasia, and Priestdaddy. I’ve also got Finding Wonders as the Middle Grade pick for DBC, though with Middle Grade being hit-or-miss for me, I’ve picked up Home Fire, the April MMD book, to start early if I finish all those or wind up DNF-ing Finding Wonders. The other MMD pick this month is Americanah which I listened to last year on audio and thought was lovely, but wasn’t going to re-read so soon.

’ve picked another ten books for March, though a bunch of books I was excited about came in at the library so I’m just barely paying lip service to #theunreadshelfproject this month. I have already finished Stay With Me (MMD March pick) and Force of Nature, the second Aaron Falk mystery from Jane Harper and its only the fifth, so the month is starting off strong. I also hope to finish Freshwater, Lab Girl (DBC), My Life On the Road (audio), I Was Anastasia, Priestdaddy, Oliver Loving, and The Hazel Wood. Of those, I own only My Life On the Road, I Was Anastasia, and Priestdaddy. I’ve also got Finding Wonders as the Middle Grade pick for DBC, though with Middle Grade being hit-or-miss for me, I’ve picked up Home Fire, the April MMD book, to start early if I finish all those or wind up DNF-ing Finding Wonders. The other MMD pick this month is Americanah which I listened to last year on audio and thought was lovely, but wasn’t going to re-read so soon.