In keeping with an unofficial “war” theme but going back in time a smidge….

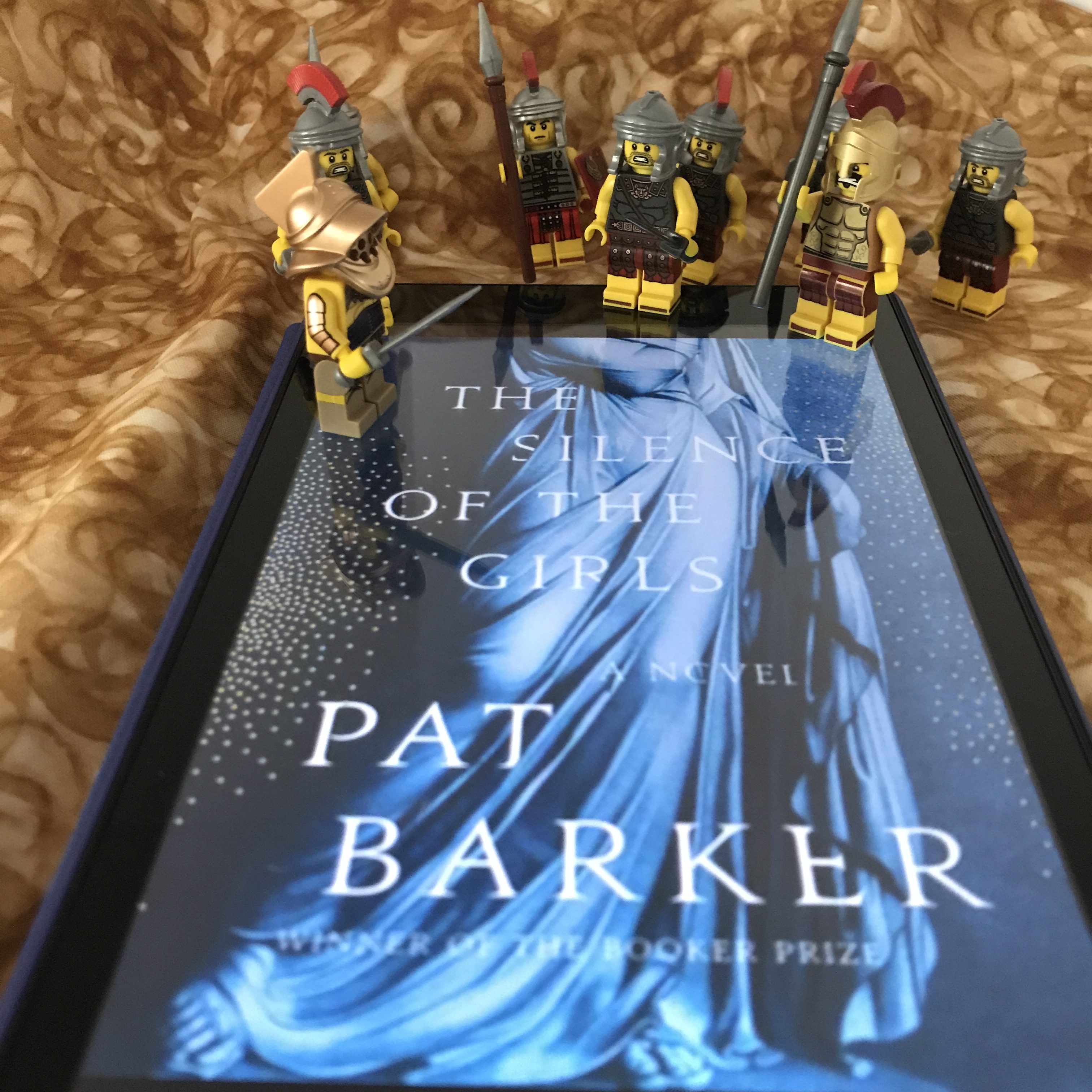

Thank you to NetGalley, Doubleday Books, and Pat Barker for the free review copy of Silence of the Girls. This book entirely captured my attention and I am happy to post this honest review.

I could still hear him pleading with Achilles, begging him to remember his own father—and then the silence, as he bent his head and kissed Achilles’s hands. “I do what no man before me has ever done, I kiss the hands of the man who killed my son.” Those words echoed round me, as I stood in the storage hut, surrounded on all sides by the wealth Achilles had plundered from burning cities. I thought: And I do what countless women before me have been forced to do. I spread my legs for the man who killed my husband and brothers.

Synopsis

Everyone has heard of Agamemnon and Achilles. Epic poems were (literally) written in their honor. But what of the women behind them? What of the women who became spoils of war? The Silence of the Girls imagines the life of Brisesis, princess of Lyrnessus and concubine of Achilles, to present the stories of the women captured, put to work, and expected to love their captors during the Trojan War. The book begins with the fall of Lyrnessus and follows Briseis until shortly after the fall of Troy and the (SPOILER ALERT) death of the greatest Greek warrior, Achilles.

Title Thoughts: Women vs. Girls

At first blush, it felt limiting to call the women taken as spoils of war “girls.” The main “girl” Briseis spends the opening chapter of the book watching her family die and then deciding whether to become a slave or throw herself off a tower. Not exactly a decision for a juvenile to be faced with. These “girls” were nightly expected to sexually service (re: were raped by) the men who had destroyed their homes and killed their brothers, husbands, fathers, and male children. To call them girls felt diminishing—“girls” has the connotation of smallness, meekness, even inconsequentiality. These were women—young women to be sure, teenagers even—but these were mothers and sex slaves and to call them anything to diminish them felt wrong.

And yet, as I read, it was easy to forget that Briseis was young—that she was a teenager, albeit a married one (normal given the time and life expectancy). It was easy to see her as older and wiser, given that her life had forced her to become so. Perhaps the title was the reminder of the youth of these women—their voices taken along with their safety, security, and- in some cases- innocence.

Stockholm Syndrome

While the events of this book predate the advent the term “Stockholm syndrome” by a few millennia, this naming is what I kept coming back to. When Briseis is taken, she does her duties out of fear that she will be cast out or even killed. Yet as the book progresses, Briseis struggles to continue to hate Achilles. As kindness is shown to her by the other women and by his best friend Patroclus, as Achilles never beats her or treats her with malice (besides generally using her as a sex slave), as she comes to see Achilles’s virtues and even his weaknesses, she finds herself caring for him.

This raised conflicting feelings—Briseis is describing Achilles to us as she comes to have changed feelings for him so it was easy for my feelings to change towards him too. Short vignettes are included from Achilles point of view beginning in Part 2, making it harder to hate him when I saw how hurt he was. I had to keep reminding myself that he was a violent killer who took women and made them his, without anything remotely resembling consent. And yet, he was a man abandoned by his mother and still obviously hurting. (Achilles needed all the therapy). He never treated Briseis as badly as he could have or as badly as others treated their slaves. But wait…as if that wins him a prize? That he wasn’t as forceful while he was raping her as he could have been? On the one hand, there is the idea that this was the time—that Achilles was only doing what was expected of him and was only receiving what was due him according to the customs of the time. But how often do we use that explanation to explain away racist grandpas, as if it’s ok that they didn’t keep up when the world changed?

It is a credit to Barker’s story telling that I still don’t know how I feel about Achilles—that she could take a character I would have assumed was black and white and made him all shades of gray. I connected to Briseis and cared for her as a character. Because I connected with her, I started to care for Achilles, though I didn’t want to and still don’t want to. This aspect of the book—the forgiving of violent men—may be something that some readers can’t accept and that will keep them from enjoying the book. That is totally valid. In some ways, I want that to be my reaction. I want this to be a place where there is no mercy for the men who stole the lives of these women, these girls. But perhaps they were hurting too. Perhaps this wasn’t the role they wanted to be filling either. And while we aren’t in ancient Greece anymore and it’s too late for Achilles, what does this say about the culture now? Are our modern day Achilleses beyond forgiveness? Is it Stockholm Syndrome or is it possible that even a violent man like Achilles can be forgiven and thus find his soul redeemed by one he violated most?*

Writing Style

While I enjoyed the story and connected to the characters, I will admit that I expected a bit more of the prose, knowing that Barker won the Man Booker and that this is a retelling of an epic poem. I wasn’t expecting dactylic hexameters, but I was expecting a bit more lyricism in the writing. Instead, the writing is on par for a solidly (3.5 star) written popular fiction novel. Perhaps the writing felt a bit pop-fiction rather than lit-fic because Briseis, though a princess and wife, was also a teenager and she was our main storyteller. The tone was conversational, a young woman confiding in friends rather than a memoirist carefully editing her words before recording them. The informal style fit the narrator and the story, it just wasn’t what I was initially expecting after hearing “Man Booker Winner.”

Recommended

Overall, this was an enjoyable read and one I recommend for readers who enjoy historical (very, very historical) popular fiction centered on female characters. This is a book to skip if you have triggers with sexual assault.

Notes

Published: September 4, 2018 by Doubleday (@doubledaybooks)

Author: Pat Barker

Date read: September 3, 2018

Rating: 3 ¾ stars

*It is never the job of the victim to forgive if he or she doesn’t want to and if doing so isn’t safe. In this context, Briseis did care about him and not because she was pressured to do so. It is from that viewpoint that I raise these questions.

Featured image credit:Jonas Jacobsson

Lifeboat 12 is also structured in three parts—Escape, Adrift, and Rescue. Escape sets up the dangerousness of life in London during the Blitzkrieg, Ken’s feeling of being unwanted by his stepmother, and the boarding and sinking of the ship. Adrift is the story of the eight days the survivors spent at sea. And Rescue is exactly what it sounds like—it is the boy’s return home, a return from the grave for their parents had been notified they had been lost at sea. While these three sections make for a hefty book—336 pages—because the story is told in verse, this was a quick read. Hood’s poetry lends the story a spare quality—the narrator is a twelve year-old boy so there are no flowery turns of phrase here. Each of the words seemed chosen for maximum impact, so that I might have only read fifty words on a page, yet the scene was as richly set and the characters as alive as if they were right next to me. The poetry also lent a more dramatic air—with portions of the book feeling as if they were pulled straight from an adventure novel.

Lifeboat 12 is also structured in three parts—Escape, Adrift, and Rescue. Escape sets up the dangerousness of life in London during the Blitzkrieg, Ken’s feeling of being unwanted by his stepmother, and the boarding and sinking of the ship. Adrift is the story of the eight days the survivors spent at sea. And Rescue is exactly what it sounds like—it is the boy’s return home, a return from the grave for their parents had been notified they had been lost at sea. While these three sections make for a hefty book—336 pages—because the story is told in verse, this was a quick read. Hood’s poetry lends the story a spare quality—the narrator is a twelve year-old boy so there are no flowery turns of phrase here. Each of the words seemed chosen for maximum impact, so that I might have only read fifty words on a page, yet the scene was as richly set and the characters as alive as if they were right next to me. The poetry also lent a more dramatic air—with portions of the book feeling as if they were pulled straight from an adventure novel.

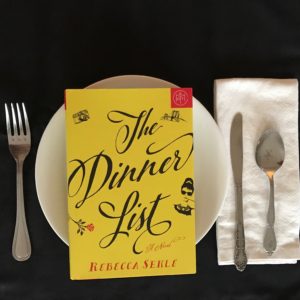

The Dinner List was a

The Dinner List was a