I’ve said many times before but I love a good WWII novel. I don’t know what it is about this time period that I find so fascinating, even after studying it for years in college. And, thanks to the DBC, I’ve actually started reading more Middle-Grade and younger YA. I saw My Real Name is Hanna and knew I had to read it. A hot second later, Lifeboat 12 popped up on Netgalley and I requested it too.

Thank you to NetGalley, Mandel Vilar Press, and Tara Lynn Masih for My Real Name is Hanna and Netgalley, Susan Hood, and Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers for Lifeboat 12. I enjoyed both books and am happy to post these honest reviews.

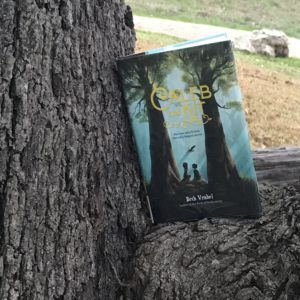

My Real Name Is Hanna

My family told stories. We swallowed them in place of food and water. Stories kept us alive in our underground sanctuary. The world continued to carry out its crimes above us, while we sought just to remain whole below.

Hanna’s story is set in Ukraine which made me assume her town would have been subject to Soviet occupation–I know significantly less about the countries that came under the rule of the Soviet Union since Between Shades of Gray is the only novel I’ve read of this time period (though I am interested in more if you want to leave me suggestions in the comments!). Instead, Hanna’s town, while briefly occupied by the Soviet army, spent more time under Nazi rule. Of course, anti-Semitism wasn’t new with the Nazis–there were already anti-Semites in town whose feelings were exploited by both the Soviets and Nazis.

The book is told in three parts—The Shtetele, The Forest, and The Caves. The Shtetle sets the stage—Hanna’s family is more privileged than many, with a nice house and a father who is respected and needed for his skills by the non-Jewish families in town. When the book opens, the war has already started but is just beginning to touch Hanna and her family. Rumors begin and mysterious people show up to hide in Hanna’s barn. Hanna is just turning fourteen—that age where so much of her remains a child still, and yet she is old enough to begin to understand what is happening. Old enough to be pulled into the secrets necessary to keep her family and her people safe.

When the town is no longer a safe place, Hanna’s family flees to the woods, to an abandoned cabin. The family has to stay inside most of the time, prepared to flee at any moment. While food was scare in the town, in the forest is where the march to hunger really begins. The family must ration food and even their own energy since they cannot consume enough calories to keep them on their feet all the time. As the Nazis move in, the family and several neighbors from a nearby cabin are forced literally underground, into an extensive network of caves.

The real family this story is based on lived the last 511 days of the war in an underground cave system, with the women and children living entirely underground, never seeing sunshine or feeling even the slightest breeze. Hanna’s family is much the same, with her father or uncle venturing out very rarely to obtain whatever food they might possibly find to bring back to the starving families below ground.

Even underground, the family lives in fear of being caught and is, at one point, walled in to the cave by townspeople. Even before this moment, many of the townspeople were not just bystanders but actively participated in the hunting down and killing–either outright or through starvation or deportation to the ghettos and camps–of their neighbors. My Real Name is Hanna is realistic in this regard and does not hide that neighbors are turning each other in. On the flip side, there are characters who help the family hide, at great cost and risk to themselves. This is perhaps the aspect of the book that may be the most troubling to younger readers—while the history here is accurate and a topic worth discussion, it is something that would require discussion with parents or other adults reading the book. May we be encouraged, and encourage younger generations, to chose to be the helpers in the face of injustice, even when the cost to ourselves is high.

Recommended

My Real Name is Hanna sits somewhat squarely in between Middle-Grade and YA (in my opinion). The audience for this book is probably right around middle school readers, with mature fourth to fifth graders able to handle the writing and themes, though too far into high school and the writing may feel a bit young for older readers. This is a book I recommend, particularly for those who are interested in areas like the Ukraine, which is featured less in WWII fiction than areas like France or even Poland yet suffered heavy losses—only 5% of Ukranian Jews survived, only 2% of Western Ukranian Jews with almost no families intact. It is a book with a powerful message of responsibility for our neighbors—this is a book to be discussed, not simply read.

Notes

Published: September 15, 2018 (September 18th for Kindle), available for pre-order now from Mandel Vilar Press

Author: Tara Lynn Masih (@taralynnmasih)

Date read: August 26, 2018

Rating: 3 ¾ stars

Lifeboat 12

Lifeboat 12 is a middle-grade novel in verse told from the point of view of a survivor of the S.S. City of Benares, a boat carrying children being evacuated from London that was sunk by a German U-Boat in September 1940.

Lifeboat 12 is also structured in three parts—Escape, Adrift, and Rescue. Escape sets up the dangerousness of life in London during the Blitzkrieg, Ken’s feeling of being unwanted by his stepmother, and the boarding and sinking of the ship. Adrift is the story of the eight days the survivors spent at sea. And Rescue is exactly what it sounds like—it is the boy’s return home, a return from the grave for their parents had been notified they had been lost at sea. While these three sections make for a hefty book—336 pages—because the story is told in verse, this was a quick read. Hood’s poetry lends the story a spare quality—the narrator is a twelve year-old boy so there are no flowery turns of phrase here. Each of the words seemed chosen for maximum impact, so that I might have only read fifty words on a page, yet the scene was as richly set and the characters as alive as if they were right next to me. The poetry also lent a more dramatic air—with portions of the book feeling as if they were pulled straight from an adventure novel.

Lifeboat 12 is also structured in three parts—Escape, Adrift, and Rescue. Escape sets up the dangerousness of life in London during the Blitzkrieg, Ken’s feeling of being unwanted by his stepmother, and the boarding and sinking of the ship. Adrift is the story of the eight days the survivors spent at sea. And Rescue is exactly what it sounds like—it is the boy’s return home, a return from the grave for their parents had been notified they had been lost at sea. While these three sections make for a hefty book—336 pages—because the story is told in verse, this was a quick read. Hood’s poetry lends the story a spare quality—the narrator is a twelve year-old boy so there are no flowery turns of phrase here. Each of the words seemed chosen for maximum impact, so that I might have only read fifty words on a page, yet the scene was as richly set and the characters as alive as if they were right next to me. The poetry also lent a more dramatic air—with portions of the book feeling as if they were pulled straight from an adventure novel.

Ken is a charming narrator—he’s a boy’s boy, obsessed with planes and always willing to give some help to a pal. Unlike most other narrators in WWII books I’ve read, Ken’s family is poor—I feel like I’ve read novels where everyone was effected by wartime rationing and scarcity, but I’m not sure I’ve read a book where the main character was poor before the book started—where liver was once or twice a week luxury. He represented an under-represented class in WWII narrators. He also doesn’t have a perfect family life—he’s fairly convinced his stepmother can’t stand him and this plan to send him to Canada is partly just to get him out of the house since she doesn’t like him. My heart ached for him when he talked about feeling unloved—while Ken does realize she cares for him by how she reacts when he comes home, my one criticism of Lifeboat 12 is that more wasn’t done with this relationship. With so many kids coming from blended families, books with boys Ken’s age who come to realize that their stepmothers really do care feel necessary.

I knew Lifeboat 12 was based on a true story, but I didn’t realize just how closely Hood stuck to the truth until I read the Author’s Note and afterward. Ken Sparks was a real survivor and the book is based on Hood’s interviews with him as well as her extensive research on the S.S. City of Benares. The Note and afterward are necessary reading—if you pick up this gem, you can’t stop reading at the end of the novel.

Recommended

Because it is so closely based on fact, I recommend Lifeboat 12 for kids (or adult middle-grade readers) who like books about historical events and adventure tales. The sinking of the S.S. City of Benares was another event I had no knowledge of—Lifeboat 12 was an enjoyable introduction to the event (if one can say learning about a devastating loss of life is in any way enjoyable). This is Hood’s first middle-grade novel after a successful career as a picture book author. I can’t wait to see where she goes next for her middle-grade-and-up readers.

Notes

Published: September 4, 2018 by Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (@simonandschuster)

Author: Susan Hood (@shoodbooks21)

Date read: September 7, 2018

Rating: 4 ¼ stars

Featured Image credit: Jonas Jacobsson

I looked up to the branches of the huge trees above me. Two long, thick trunks soared straight to the sky and then curved away from each other. I had heard once about trees that do that—live side by side but bend away to share the sun. They are buddies. They could stick close, but if they do, eventually one will struggle to tower over the other, keeping the weaker, unluckier one in the shade. Instead if they’re really friends, they’ll bend apart. I wondered if it hurt, twisting away from your friend like that.

I looked up to the branches of the huge trees above me. Two long, thick trunks soared straight to the sky and then curved away from each other. I had heard once about trees that do that—live side by side but bend away to share the sun. They are buddies. They could stick close, but if they do, eventually one will struggle to tower over the other, keeping the weaker, unluckier one in the shade. Instead if they’re really friends, they’ll bend apart. I wondered if it hurt, twisting away from your friend like that. Sarah Nickerson is living life at break-neck speed, working eighty-hour work weeks and mothering three children. Until suddenly the multitasking catches up to her, causing an accident that leaves Sarah with “left neglect”—a brain injury that causes her to entirely forget her left side even exists. As Sarah trains her brain to pay attention to a part of herself she’s never had to focus deliberate energy on, she is also forced to reckon with other areas of her life left long neglected, including her relationship with her mother.

Sarah Nickerson is living life at break-neck speed, working eighty-hour work weeks and mothering three children. Until suddenly the multitasking catches up to her, causing an accident that leaves Sarah with “left neglect”—a brain injury that causes her to entirely forget her left side even exists. As Sarah trains her brain to pay attention to a part of herself she’s never had to focus deliberate energy on, she is also forced to reckon with other areas of her life left long neglected, including her relationship with her mother.

Synopsis

Synopsis Summary

Summary Synopsis

Synopsis