I received a digital ARC of this book from Knopf on NetGalley. I’m grateful to Knopf for their generosity and, because I enjoyed the book, was happy to post this honest review. All opinions are my own.

She thought of herself as little fragments drifting into the universe into tiny pieces and then she thought of each little fragment as separate and singular to herself, and she could not tell if she were only the fragments or if she were ever anything bigger than that….The last thing she heard was the sound of her own heartbeat, improbably consistent, uniquely her own…The sound of her heart to herself, a sound she’d heard so many times, as sound she barely ever listened to.

Synopsis

Leda is a Boston college student, a daughter, a postgrad, a fiancé in love, a young mother, middle-aged, and then elderly. The Girl Who Never Read Noam Chomsky follows the lifecycle of a woman just beginning her life until she closes her eyes for the last time. In the intervening decades, Casale takes us on a journey of what it means to come of age and then to simply age in a time when what it means to be a woman is constantly in flux.

Identity

At it’s heart, The Girl Who Never Read Noam Chomsky is about the woman we envision ourselves to be when we are young—not as children, but in those college formative years, when the world feels open and full of possibility (assuming of course that you are at least middle class and white—this book probably isn’t going to appeal to you if you aren’t). As a result of this focus, this book made me uncomfortable, not because of any particular topic touched upon by Casale or even any particular choice Leda makes, but rather, because she reminded me of a time in my life when I wasn’t sure who I was—something that was frankly true until about four years ago. I could be the girl who reads Noam Chomsky. Or, more likely at nineteen, I can be the girl who sees someone reading the book and wants to be the girl who reads Noam Chomsky. The girl who wants that to be how people think of her. Like Leda with the Chomsky book, I carried around an idea of who I was and who I wanted to be for a long time, until life circumstances forced me to accept that the idealized version of myself I was trying to be was killing me. My Noam Chomsky had become the albatross around my neck. We do eventually see Leda settle in to her own skin, though there are times when it is clear that maybe that isn’t something that’s fully possible—there is always someone you’re trying to be, some version of yourself that you want to grow into.

Time

Casale makes a slightly unusual choice for a coming-of-age novel—unlike most novels of this type, Leda is always coming of age—we follow her from one life stage to the next into old age. There is no end to Leda’s growth, she never arrives at any particular, set point and specifically never becomes the woman who reads Noam Chomsky. The decision to follow Leda through her entire adult life is interesting—the book spans the decades of her entire life, meaning there were times I connected to her and then we passed that point where I could. Indeed, by the sheer nature of the passage of time and changes of Leda, it is hard to imagine that any one reader can fully identify with her. At some point, Leda’s life experiences so outpaced mine that it went from feeling as if I were chatting with a friend over coffee to watching a movie purely as a bystander, with no direct engagement. This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing—by the time Leda’s life experiences passed mine, I cared enough about her to keep reading to see where she ended up. I just couldn’t relate any more.

This sprawling narrative did mean that time passed rather more quickly at the end, and I don’t love a novel that accelerates significantly in the last chapters. It was also somewhat awkward in the writing of these last chapters because I thought of Leda as being around my age, placing the end chapters in a future at least forty years from now. With the rate at which technology is developing and changing the way we interact, it meant the Casale had to keep some of the background and action here necessarily vague. This wasn’t a novel about the future—it was a novel about growth that by necessity had scenes in an unknown future. Casale had taken Leda so far that she was almost duty-bound to finish with her, but the constraints of the unknown future impacted these chapters and gave them less depth than the more hearty chapters in the middle of the book.

Feminism

In a world where woman are told to stand up for themselves and to stop apologizing, it is easy to feel as if the expectations of being a feminist are just as hard to fulfill as the ones we’re supposed to be escaping from. Casale captures this tension with Leda—Leda shouldn’t want to move across the country for her partner’s job, and yet she does. Does this make her a bad feminist? When she has a daughter, she doesn’t want her daughter to want the Barbies, but is it feminist or anti-feminist to steer her away from what she loves to something less symbolic of the constraints of womanhood we are supposed to be escaping from? Sometimes being a woman is exhausting—you will almost certainly always being disappointing someone on both ends of the spectrum here, too burn-your-bra for the patriarchy but still too barefoot-and-pregnant for the feminists. It is simultaneously a liberating and constraining time to be alive and Casale captures this tension in relatable ways with Leda’s development.

Style

The initial choppy writing style threw me off at first and if this weren’t a book I had gotten on Netgalley and felt I had to push through to review, I likely would have stopped after a chapter or two. As Leda ages, her voice becomes more confident and the choppy style diminishes, settling into a more readable rhythm. All that to say, the writing isn’t going to win any awards but the style choices that make it more difficult to read initially do fade into a more standard, flowing narrative. It is nowhere near as terrible as Lilac Girls, my evergreen measuring stick for subpar writing. Casale really started to hit her stride for me when she started describing the pretentious hipsters who populated Leda’s writing seminar in Chapter Six—the chapters are short and it is worth pushing through to this point. I’m not usually a proponent of pushing through if you don’t have to, but I do think this book takes some time to settle in to and it’s fair to give it at least eighty pages before you decide to abandon Leda.

Verdict?

In the end, this is a book that I wound up enjoying and would rate as better than average. I wouldn’t recommend this book widely, rather its one of those books that I would recommend to specific people after knowing them and having a feel for their reading lives.

Notes

Published: April 17, 2018 by Knopf (@aaknopf) available for pre-order now

Author: Jana Casale (@janacasale)

Date Read: January 27, 2018

Rating: 3 ¼ stars

Synopsis

Synopsis All around Roy were shards of a broken life, not merely a broken heart. Yet who could deny that I was the only one who could mend him, if he could be healed at all? Women’s work is never easy, never clean.

All around Roy were shards of a broken life, not merely a broken heart. Yet who could deny that I was the only one who could mend him, if he could be healed at all? Women’s work is never easy, never clean.

Synopsis: He Said/She Said follows Kit and Laura, alternating between their early days of dating to today, ten plus years’ married. Kit is a solar eclipse chaser and, at one of the first festivals where he invites Laura into the fold, Laura interrupts a rape. The repercussions of that rape and the interruption are continuing some fifteen years later when Kit breaks their years of hiding to travel for another eclipse, leaving Laura pregnant at home.

Synopsis: He Said/She Said follows Kit and Laura, alternating between their early days of dating to today, ten plus years’ married. Kit is a solar eclipse chaser and, at one of the first festivals where he invites Laura into the fold, Laura interrupts a rape. The repercussions of that rape and the interruption are continuing some fifteen years later when Kit breaks their years of hiding to travel for another eclipse, leaving Laura pregnant at home. Synopsis: We Are Okay follows Marin, a college student at an unnamed college in New York as she prepares to stay in the dorms over the Winter Break. As you come to learn through Marin’s flashbacks and conversations with a high-school friend/possible former sweetheart who has come to visit, Marin has no other home, having lost her grandfather shortly before she was to start college. The novel explores the reaches of grief, though as the reader comes to understand, Marin’s grief is complicated by the complicated person she discovered her grandfather to be only upon his death.

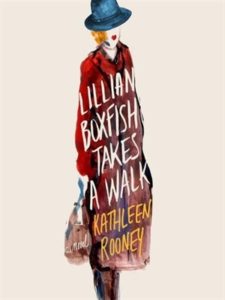

Synopsis: We Are Okay follows Marin, a college student at an unnamed college in New York as she prepares to stay in the dorms over the Winter Break. As you come to learn through Marin’s flashbacks and conversations with a high-school friend/possible former sweetheart who has come to visit, Marin has no other home, having lost her grandfather shortly before she was to start college. The novel explores the reaches of grief, though as the reader comes to understand, Marin’s grief is complicated by the complicated person she discovered her grandfather to be only upon his death. Synopsis: On the last night of 1983, Lillian Boxfish finds herself taking a walk through New York City, reminiscing the good times and the bad, remembering what she was like as the highest paid woman ad-writer of her time, as a poet, as a broken woman, and as she is now—not entirely whole, not entirely all-right, but certainly not like any old lady you know.

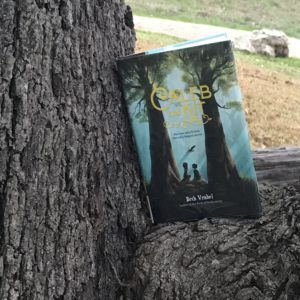

Synopsis: On the last night of 1983, Lillian Boxfish finds herself taking a walk through New York City, reminiscing the good times and the bad, remembering what she was like as the highest paid woman ad-writer of her time, as a poet, as a broken woman, and as she is now—not entirely whole, not entirely all-right, but certainly not like any old lady you know. I looked up to the branches of the huge trees above me. Two long, thick trunks soared straight to the sky and then curved away from each other. I had heard once about trees that do that—live side by side but bend away to share the sun. They are buddies. They could stick close, but if they do, eventually one will struggle to tower over the other, keeping the weaker, unluckier one in the shade. Instead if they’re really friends, they’ll bend apart. I wondered if it hurt, twisting away from your friend like that.

I looked up to the branches of the huge trees above me. Two long, thick trunks soared straight to the sky and then curved away from each other. I had heard once about trees that do that—live side by side but bend away to share the sun. They are buddies. They could stick close, but if they do, eventually one will struggle to tower over the other, keeping the weaker, unluckier one in the shade. Instead if they’re really friends, they’ll bend apart. I wondered if it hurt, twisting away from your friend like that. Sarah Nickerson is living life at break-neck speed, working eighty-hour work weeks and mothering three children. Until suddenly the multitasking catches up to her, causing an accident that leaves Sarah with “left neglect”—a brain injury that causes her to entirely forget her left side even exists. As Sarah trains her brain to pay attention to a part of herself she’s never had to focus deliberate energy on, she is also forced to reckon with other areas of her life left long neglected, including her relationship with her mother.

Sarah Nickerson is living life at break-neck speed, working eighty-hour work weeks and mothering three children. Until suddenly the multitasking catches up to her, causing an accident that leaves Sarah with “left neglect”—a brain injury that causes her to entirely forget her left side even exists. As Sarah trains her brain to pay attention to a part of herself she’s never had to focus deliberate energy on, she is also forced to reckon with other areas of her life left long neglected, including her relationship with her mother. Synopsis

Synopsis Timing

Timing Synopsis

Synopsis