Synopsis

The Line Becomes A River is a memoir of Francisco Cantu’s short time with the border patrol, both as a boots-on-the-ground agent and as an intelligence officer. In the years after he left, Cantu befriended an undocumented man and his family—the last third of the book is the story of his interactions with them and the immigration system. Peppered throughout the memoir are policy and historical vignettes about the border.

Conflict

Conflict

I am having a hard time deciding how I feel about The Line Becomes a River. Before I read it, I knew that activists had disrupted his planned appearance at BookPeople in Austin, protesting his making money off of his experience in the Border Patrol tearing families apart. The impression I had from the article was that at least some of these people hadn’t read the book and were protesting the fact that he had participated in the Border Patrol at all, destroying families and being complicit in the system that has caused thousands of deaths of individuals trying to cross in the deserts at the hands of unscrupulous coyotes. I get this criticism but if individuals who participated in the Border Patrol are not allowed to tell their stories (which would seem to be the logical end of this argument), then we never hear from an entire side of people about what’s going on in on the ground in one of the most contentious, debated places in this country. Having read The Line Becomes a River and listened to how Cantu was unable to continue his work, how he was not able to keep participating in this system, I am less concerned with protesting this aspect of the book.

My biggest concern with this book—and the one that makes me say this is either a four-star read or a one-star read—is that the entire last third of the book tells the story of Cantu’s friend Jose—but I have no idea whether Cantu had permission to tell this story. After leaving the Border Patrol, Cantu works at a coffee shop while studying for his maters degree and befriends a man named Jose Martinez. Jose is undocumented, though he has been in the country long enough to benefit from deferred action against him if he doesn’t leave…except his mother living in Mexico is dying so he does what any family man would do and he leaves. His is apprehended on his way back and Cantu throws himself into trying to help Jose with an immigration claim, including long trips to take Jose’s sons to see him in detention. During this section, Cantu reads from letters submitted by Jose’s friends and family as part of his immigration claim. It was at this point that serious questions arose for me as to whether Cantu had permission to tell this story. While it would be an invasion of Jose’s privacy to tell some of this story before this point, Cantu was speaking of his own experience, of things within his own knowledge. When he begins to read the letters, the only way Cantu could do this is if he copied them, intending them for this kind of use since the letters intended recipient was the immigration judge and its not clear Cantu had permission to read them, much less copy and reproduce them in a book he will benefit monetarily from. I have searched and cannot find the answer, though the fact that Cantu is silent in his thanks and afterward about Jose makes me worry he did not have permission. If anyone can find this answer, I’d love to be able to settle on how I feel about this book.

But Four Stars?

From a purely literary standpoint, the book is marvelously done. I listened to the audio, read by the author. While I can’t recommend him for a second career as an audiobook performer, he did well with his book—lending weight where he wanted it, though the reading was a bit more halting than polished at points. He intersperses his narrative with facts and vignettes from social science studies, providing historical and policy frames of reference for his personal experience. He is a masterful writer of his own experience—his writing is simultaneously beautiful and haunting in places while also being relatable, even for someone who has no personal experience of any kind with the border. It is like nothing else I have ever read and it feels like a necessary read for a layperson trying to understand the border debates.

Morality and Solutions

At its heart, The Line Becomes a River is a memoir—Cantu doesn’t claim to be making wide-reaching arguments about the Border Patrol or immigration policy and enforcement except to be saying that the system doesn’t work—an argument that anyone can agree with (albeit for different reasons) regardless of your place on the political spectrum. As with any police force, the Border Patrol pulls people who want to be kind and fair (Cantu paints himself this way) as well as the bad apples who lean toward the sadistic, and the full-range of the spectrum in between. Indeed, embedded within Cantu’s narrative here are confessions of cruelties that even he commits—destroying caches of migrants’ water and food so that when they return for their water in the blistering, deathly desert, they will find none and be motivated to turn themselves in. Glossed over here is the equally likely choice they will make to press on—desperate people do desperate things and no one crosses the border in a desert without desperation driving them.

As someone who lives in Texas, the border debates feel literally close to home. Living in Austin (the blueberry in the tomato soup, if you’re inclined to gross culinary metaphors), the political bent I’m exposed to tends towards the more liberal. I have clients who will be impacted by the loss of DACA and know people who were at one time illegally in this country. There is a fierce debate raging over the treatment of a detainee who has been sexually assaulted at a detention center approximately thirty minutes from here. In this sense, my only frustration is that Cantu doesn’t go farther in his book and suggest a solution. This is laudable on the one hand, since The Line Becomes a River doesn’t become Hillbilly Elegy with its gross over-allegories. On the other hand, the I want a solution. I don’t know that I want an up-close version of both sides of the debate with no idea how to solve it.

Summary

Because it is not clear whether he had permission, it is hard for me not to feel like this book is, as the protestors at BookPeople alleged, exploitative. While I am not pro-Border Patrol in its current form, I think there is value in Cantu’s story of his experiences—how else do we learn what is really going on there if not from someone who was on the inside—especially someone who is able to see that what he did was not ethical. But here is the line for me—it is one thing for Cantu to be complicit in the system and write to expose that system. It is another to befriend a specific person and then exploit him to the extent Cantu does in the last third of his book if he did not have permission to tell this story. Where the macro exploitation seems excusable for the larger good of exposing this story, the micro hits too close to home for me to make excuses for Cantu as a writer. This ultimately isn’t a book I can recommend in good conscience without knowing the answer to whether Jose granted Cantu permission to share this intimate portrait of his life.

Notes

Published: February 6, 2018 by Riverhead Books (@riverheadbooks)

Author: Francisco Cantu

Date read: March 27, 2018

Rating:1 or 4 stars

Coates’s most recent offering is a compilation of the essays he wrote for The Atlantic during the eight years of Obama’s presidency, one per year, with commentary of what was going on in his life and the life of many black Americans during each of the eight years. Because the essays were originally magazine articles, there is some repetition among them of certain points or common phrases that, if this were a book of essays, would likely have been edited to fit better. None of the thoughts or arguments that were repeated were long, so the repetition didn’t bother me as a reader, nor did it cause me to go into skim mode. It was just noticeable. The introductions to each article were interesting in that, while the context was helpful, Coates also comments on the following article—things he wished he had done differently, whether some of his points or predictions held up, and general criticism of his work. As a reader, this was a strange device and it made me wish that the “intro” essays followed the pieces instead. His critique of his own work colored how I read the article and I wished before some of them that I had a chance to form my opinion before reading his hindsight-critique.

Coates’s most recent offering is a compilation of the essays he wrote for The Atlantic during the eight years of Obama’s presidency, one per year, with commentary of what was going on in his life and the life of many black Americans during each of the eight years. Because the essays were originally magazine articles, there is some repetition among them of certain points or common phrases that, if this were a book of essays, would likely have been edited to fit better. None of the thoughts or arguments that were repeated were long, so the repetition didn’t bother me as a reader, nor did it cause me to go into skim mode. It was just noticeable. The introductions to each article were interesting in that, while the context was helpful, Coates also comments on the following article—things he wished he had done differently, whether some of his points or predictions held up, and general criticism of his work. As a reader, this was a strange device and it made me wish that the “intro” essays followed the pieces instead. His critique of his own work colored how I read the article and I wished before some of them that I had a chance to form my opinion before reading his hindsight-critique. The focus of probably the first half of When They Call You a Terrorist was not what I expected since Khan-Cullors’s recollections seemed more about her brother’s experience with an inadequate public and prison mental health system than it did on her brother’s blackness. Which is not to say that his blackness was ignored or even that his blackness didn’t greatly affect the way the mental health and law enforcement systems responded to him. I simply didn’t know much about Khan-Cullors before listening (I think literally the only thing I could recall hearing about was her partner’s being detained trying to come into the country from Canada) and so did not expect the lengthy discussion of mental illness. Her compassion for her brother and the way the family tried to treat him and have others treat him with as little force as possible made me hurt for her. (Khan-Cullors reads the book herself, which added to the tragedy inherent in many of the sections.) Because so much of the first half of the book is simultaneously a study of being black and having a mental illness, I would go so far as to say that if you’re interested in hearing about the lived experience of trying to obtain mental health care in a broken system, this is a powerful book for that alone.

The focus of probably the first half of When They Call You a Terrorist was not what I expected since Khan-Cullors’s recollections seemed more about her brother’s experience with an inadequate public and prison mental health system than it did on her brother’s blackness. Which is not to say that his blackness was ignored or even that his blackness didn’t greatly affect the way the mental health and law enforcement systems responded to him. I simply didn’t know much about Khan-Cullors before listening (I think literally the only thing I could recall hearing about was her partner’s being detained trying to come into the country from Canada) and so did not expect the lengthy discussion of mental illness. Her compassion for her brother and the way the family tried to treat him and have others treat him with as little force as possible made me hurt for her. (Khan-Cullors reads the book herself, which added to the tragedy inherent in many of the sections.) Because so much of the first half of the book is simultaneously a study of being black and having a mental illness, I would go so far as to say that if you’re interested in hearing about the lived experience of trying to obtain mental health care in a broken system, this is a powerful book for that alone. Admittedly, of the three books featured here, this one probably made me the most uncomfortable, but mostly because I don’t read very many books that prominently feature essays about labia and vibrators. Which, let me quickly add, were not mentioned for shock value—this wasn’t a book that I felt like I wanted to put down because it veered into the gross-Lena-Dunham-esque territory. There were just a few moments of “oh—I don’t know that I’d talk about that publicly but here we go.” I will say, this book probably made me the most uncomfortable of the three, though it was an uncomfortable that, like

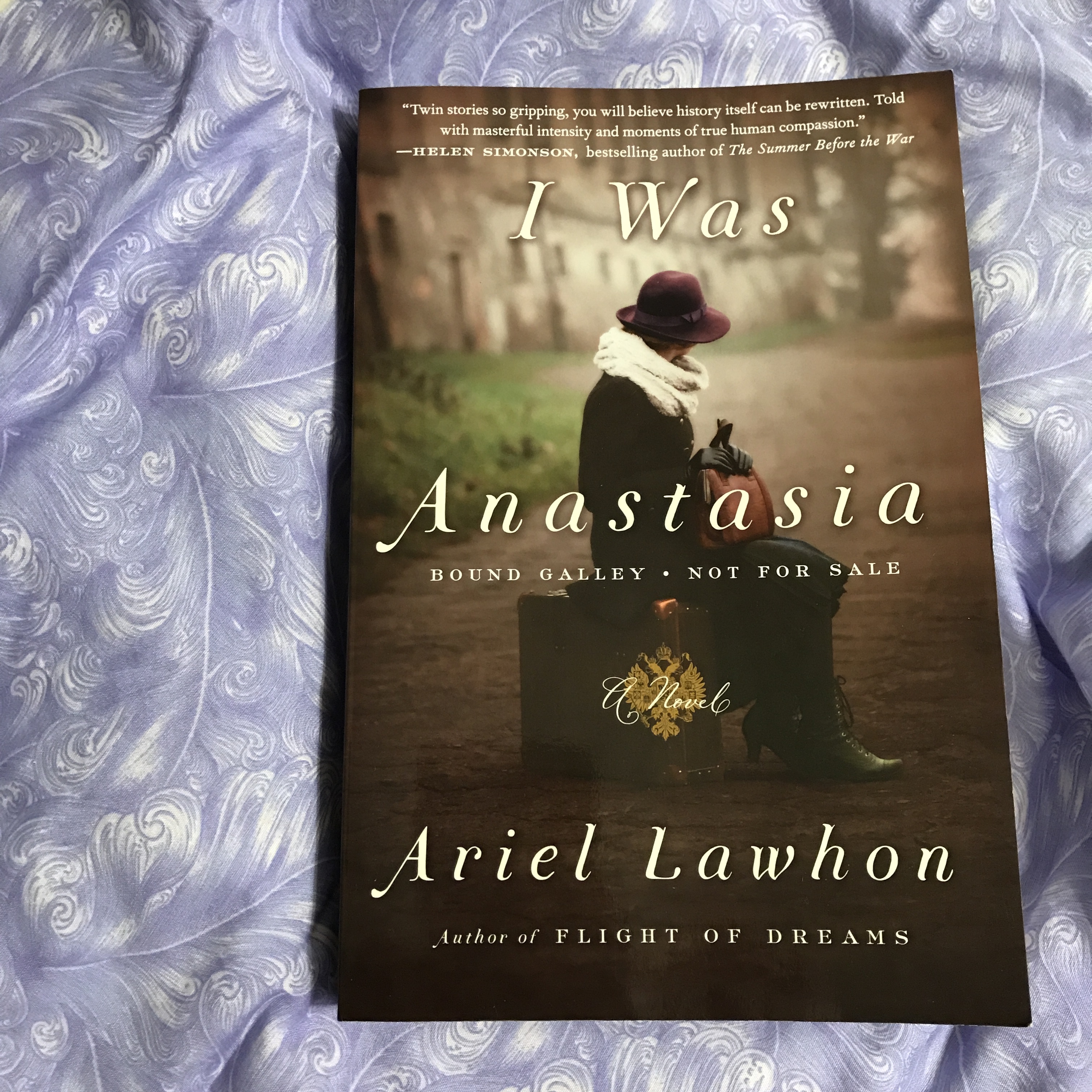

Admittedly, of the three books featured here, this one probably made me the most uncomfortable, but mostly because I don’t read very many books that prominently feature essays about labia and vibrators. Which, let me quickly add, were not mentioned for shock value—this wasn’t a book that I felt like I wanted to put down because it veered into the gross-Lena-Dunham-esque territory. There were just a few moments of “oh—I don’t know that I’d talk about that publicly but here we go.” I will say, this book probably made me the most uncomfortable of the three, though it was an uncomfortable that, like  If I tell you what happened that night in Ekaterinburg I will have to unwind my memory—all the twisted coils—and lay it in your palm. It will be the gift and the curse I bestow upon you. A confession for which you may never forgive me. Are you ready for that? Can you hold this truth in your hand and not crush it like the rest of them?…But, like so many others through the years, you have asked:

If I tell you what happened that night in Ekaterinburg I will have to unwind my memory—all the twisted coils—and lay it in your palm. It will be the gift and the curse I bestow upon you. A confession for which you may never forgive me. Are you ready for that? Can you hold this truth in your hand and not crush it like the rest of them?…But, like so many others through the years, you have asked: Synopsis

Synopsis Synopsis

Synopsis

When Anne Bogel chose Interpreter of Maladies as her flight pick for This Must Be The Place, I was pleased. I’ve owned this book and hadn’t had a chance to read it yet (#storyofmylife) and really enjoyed The Namesake when I read it several years ago. I’m glad I read Interpreter of Maladies, though I didn’t love it as much as I wanted to.

When Anne Bogel chose Interpreter of Maladies as her flight pick for This Must Be The Place, I was pleased. I’ve owned this book and hadn’t had a chance to read it yet (#storyofmylife) and really enjoyed The Namesake when I read it several years ago. I’m glad I read Interpreter of Maladies, though I didn’t love it as much as I wanted to. All around Roy were shards of a broken life, not merely a broken heart. Yet who could deny that I was the only one who could mend him, if he could be healed at all? Women’s work is never easy, never clean.

All around Roy were shards of a broken life, not merely a broken heart. Yet who could deny that I was the only one who could mend him, if he could be healed at all? Women’s work is never easy, never clean.

Synopsis: He Said/She Said follows Kit and Laura, alternating between their early days of dating to today, ten plus years’ married. Kit is a solar eclipse chaser and, at one of the first festivals where he invites Laura into the fold, Laura interrupts a rape. The repercussions of that rape and the interruption are continuing some fifteen years later when Kit breaks their years of hiding to travel for another eclipse, leaving Laura pregnant at home.

Synopsis: He Said/She Said follows Kit and Laura, alternating between their early days of dating to today, ten plus years’ married. Kit is a solar eclipse chaser and, at one of the first festivals where he invites Laura into the fold, Laura interrupts a rape. The repercussions of that rape and the interruption are continuing some fifteen years later when Kit breaks their years of hiding to travel for another eclipse, leaving Laura pregnant at home. Synopsis: We Are Okay follows Marin, a college student at an unnamed college in New York as she prepares to stay in the dorms over the Winter Break. As you come to learn through Marin’s flashbacks and conversations with a high-school friend/possible former sweetheart who has come to visit, Marin has no other home, having lost her grandfather shortly before she was to start college. The novel explores the reaches of grief, though as the reader comes to understand, Marin’s grief is complicated by the complicated person she discovered her grandfather to be only upon his death.

Synopsis: We Are Okay follows Marin, a college student at an unnamed college in New York as she prepares to stay in the dorms over the Winter Break. As you come to learn through Marin’s flashbacks and conversations with a high-school friend/possible former sweetheart who has come to visit, Marin has no other home, having lost her grandfather shortly before she was to start college. The novel explores the reaches of grief, though as the reader comes to understand, Marin’s grief is complicated by the complicated person she discovered her grandfather to be only upon his death. Synopsis: On the last night of 1983, Lillian Boxfish finds herself taking a walk through New York City, reminiscing the good times and the bad, remembering what she was like as the highest paid woman ad-writer of her time, as a poet, as a broken woman, and as she is now—not entirely whole, not entirely all-right, but certainly not like any old lady you know.

Synopsis: On the last night of 1983, Lillian Boxfish finds herself taking a walk through New York City, reminiscing the good times and the bad, remembering what she was like as the highest paid woman ad-writer of her time, as a poet, as a broken woman, and as she is now—not entirely whole, not entirely all-right, but certainly not like any old lady you know. I looked up to the branches of the huge trees above me. Two long, thick trunks soared straight to the sky and then curved away from each other. I had heard once about trees that do that—live side by side but bend away to share the sun. They are buddies. They could stick close, but if they do, eventually one will struggle to tower over the other, keeping the weaker, unluckier one in the shade. Instead if they’re really friends, they’ll bend apart. I wondered if it hurt, twisting away from your friend like that.

I looked up to the branches of the huge trees above me. Two long, thick trunks soared straight to the sky and then curved away from each other. I had heard once about trees that do that—live side by side but bend away to share the sun. They are buddies. They could stick close, but if they do, eventually one will struggle to tower over the other, keeping the weaker, unluckier one in the shade. Instead if they’re really friends, they’ll bend apart. I wondered if it hurt, twisting away from your friend like that. Sarah Nickerson is living life at break-neck speed, working eighty-hour work weeks and mothering three children. Until suddenly the multitasking catches up to her, causing an accident that leaves Sarah with “left neglect”—a brain injury that causes her to entirely forget her left side even exists. As Sarah trains her brain to pay attention to a part of herself she’s never had to focus deliberate energy on, she is also forced to reckon with other areas of her life left long neglected, including her relationship with her mother.

Sarah Nickerson is living life at break-neck speed, working eighty-hour work weeks and mothering three children. Until suddenly the multitasking catches up to her, causing an accident that leaves Sarah with “left neglect”—a brain injury that causes her to entirely forget her left side even exists. As Sarah trains her brain to pay attention to a part of herself she’s never had to focus deliberate energy on, she is also forced to reckon with other areas of her life left long neglected, including her relationship with her mother. Synopsis

Synopsis